The light is already there. The shadows are already there.

Category

Discussions and viewpoints

Author

Leth & Gori

Interview by Louise Grønlund

Photography

Laura Stamer

Date

04 Mar 2021

Share

Copy

This interview unfolds and enhances some of the most central themes that were described in the Daylight talk with LETH & GORI. With the same engagement and enthusiasm, Uffe Leth and Karsten Gori reflect, clarify and expand their approach to architecture in discussions on Nordic light, apertures for daylight, the colour and daylight, their heroes and finally, how they relate to the new ‘turn’ in architecture, described by Mari Hvattum, as the Perceptual turn.

Q: In some of the questions after your lecture, there was a strong focus on the significance of the specific appearance of daylight in the Nordic countries, and especially in Denmark, where all your projects are located. Can you elaborate on what kind of awareness you have of these basic daylight conditions in both your process and the design of a project?

A: It was very nice that some of the questions addressed the geographic difference in daylight, because it gave us the opportunity to reflect on daylight as something very local, personal and site-specific. By working with light as a natural part of the context and site-specific qualities, you are forced to study it on the same level as other important site-related topics like, the landscape, the trees, the wind etc. This way, light becomes very specific, present and physical in the project. So, to answer the question, we would probably not focus so much on the geographical location, but rather on the specific place and the light of this place. Our point of departure is always that no place is empty. The light is already there. The shadows are already there. The land, the city, the people. They are all basic conditions of the site on which a project is built.

Q: Your definition of a place with its light is very precise: “The light is already there. The shadows are already there”. In the book “Nightlands”, Christian Norberg-Schulz unfolds his thoughts on the characteristic of the light in the North as “Nordic light thus creates a space of moods. In the North, we occupy a world of moods, of shifting nuances, of never-resting forces – even when the light is withdrawn and filtered through an overcast sky”(1). Can you recognise that way of portraying and experiencing the Nordic light? And if so, how do you embrace or enhance these daylight conditions in your projects?

A: The other day, I (Karsten) drove through the hilly landscapes of Northern Jutland in Denmark just before sunset. It had been a cloudy day, completely overcast. The air and the soil seemed to be filled with moisture – as if the land were breathing. When the sun had set, it seemed the light decided to stay longer. As if the light had been ‘caught’ in the damp air, encapsulated in the moisture, the entire landscape was suddenly radiating an almost invisible light, endless numbers of grey nuances constantly shifting and dancing above the landscape, blurring the horizon. It his text, Norberg-Schulz puts it this way: “Suddenly, the soil begins to glisten; light which saturates southern space, here (in the North, red.) seems to emanate from things themselves. (2)

When working on the plan layout of our projects, we try to allow for the shifting light – “the world of moods, of never-resting forces”, as Norberg-Schulz writes, to enter the spaces, rooms and corners of the plan.

In this understanding the architectural plan is very much about movement. The movement of the inhabitant(s) of space, but also the movement of light. Enfilade spaces where light enters from the side, each space being coloured in its own light. Through-light situations where the light from the North, South, East and West are allowed to blend. Light brought into the deepest spaces of the plan by means of skylights, lightwells or light courts. Allowing light to open corners and erode the plan. In the architectural plan, we investigate how the light can ‘flow’ through the building and how light can interact with the use and everyday life of rooms and spaces. The movement of shifting light.

Another way of accommodating the shifting nuances of the Nordic light and keep or maybe even ‘collect’ the sparse daylight in the Nordic countries, is in the architectural detailing of openings and apertures. Think of the profiling of a historic window and how the fine detailing and profiles manage to ‘bend’ the light into space, making the light softer and richer. Almost magically, the profiles and detailing of the window capture and make the light stay in a space for a few more moments. This way of dealing with light makes us think of two beautiful projects in Stockholm, Sweden: Gunnar Asplund’s Stadsbibioteket (City Library) and Johan Celsing’s church in Årsta. In both projects, the detailing and shifted position of the wall opening and the window frame create a new in-between space for light to fill and rest – in between, outside and inside. As if the light ‘lives’ in the wall.

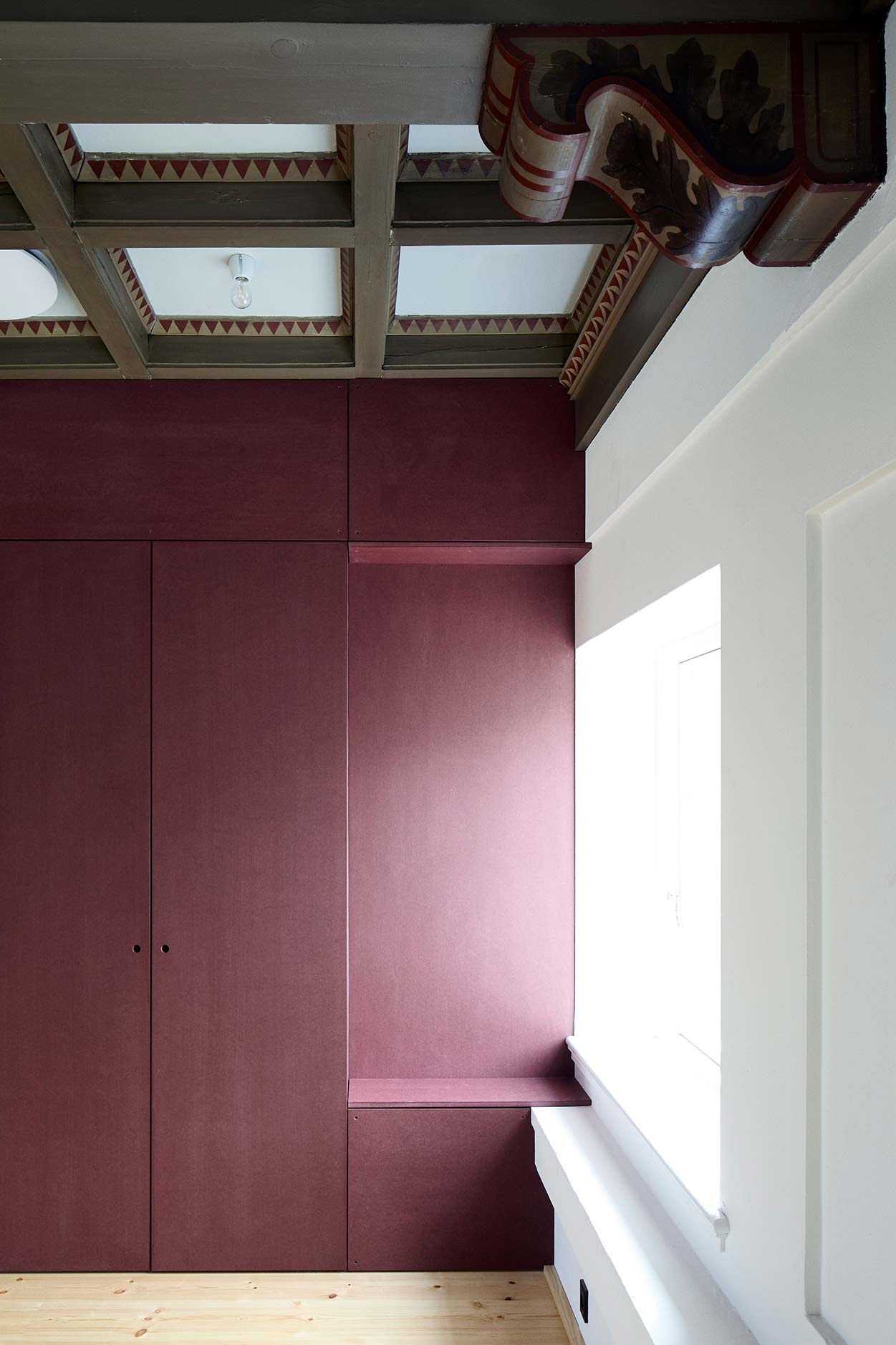

In our project ‘Elefanthuset’, we turn the daylight into a morphological spatial and erosive force that carves and excavate corners and spaces into walls and furniture for the daylight to inhabit.

Q: In many of your projects there are skylights in different forms, shapes and materials. They also appear in buildings of very different programmes.

Can you describe your intentions and considerations when using skylights?

A: We use of skylights in various shapes and with different spatial and functional goals in mind. In a project like Roof House, the skylights create a series of different situations. Besides providing spaces of light, they expand spaces upwards and create new spaces on the roof level.

In addition, the interventions in the existing roof and façade of the Roof House project create a richness of different situations of light and shadows that we discussed above.

Another example is the small Ballet Dancers House that we also talked about in the lecture. In this project, the local planning rules only made it possible to build a 90 m2 house on the site, so here the strategy became to increase the space upwards by giving each room its own skylight roof.

The skylights in projects like Roof House and Ballet Dancers House are, of course, about providing spatial sequences with an abundance of daylight. But they also establish a direct dialogue with the outside and the possibility of following the changes in light, the sun, clouds, the treetops, and the stars. In the Danish contribution to the 2016 Biennale Architettura in Venice titled ‘The Art of Many’, the curators included a category of projects under the title Beyond Luxury which discussed an ideological shift in the notion of luxury from ‘bling’ to qualities like light, space, materiality and dialogue between the inside and the outside. This is a kind of richness (or luxury) that we seek in all our projects, and the roofscapes, skylights and general work with light and space are an important part of that work.

Q: And in relation to this question: What kind of considerations do you have on the different daylight appearances that a skylight creates as opposed to a daylight opening in a wall?

And how do you design with those two very different daylight apertures?

A: Openings and apertures are of course necessary in order to bring daylight into our buildings. But we also consider the openings and apertures in roofs or walls as spaces for the light to inhabit. Spaces that contain light. Light vessels. Sometimes, we even discuss the daylight as a ‘fifth inhabitant’ – an almost physical actual character that needs its own spaces and quarters to wander around in. The client of course needs spaces for various programmes, a kitchen, for example, or closet or breakfast room. But the client also has to share the space with the light – and this sometimes takes a little bit of explanation in order for the client to accept and really enjoy!

We are often looking for ways to ‘double programme’ wall openings, so they also become places to rest or stay. A sofa in the window, a work place or a kitchen sink, so that the inhabitant can share the window space with the light. The aperture of the skylight on the other hand creates a space that is not accessible to us, but only to the light – or maybe also to our thoughts and imagination to flow.

Q: In “Goethe´s Colour Theory”,he reflects on and describes the relation between colours and light:

“The colours are the actions of light – actions and disorders. In this sense, we can expect information about the light from the colours”(3)

Taking the words of Goethe into consideration: In which way do you decide where to place painted surfaces in or nearby windows? For example: Orientation, view to the exterior, programme etc.?

A: We are primarily interested in the phenomenological qualities of the individual materials. Their inherent performative qualities, robustness, roughness, smoothness, reflection and colour.

In many of our projects, the construction of space is the result of ‘the order’ of architecture; the stacking of elements, columns, pillars and walls and the closing of space; beams, lintels, frames etc.

The anatomy of architecture is also an interest in the layering of walls and roof constructions, from the inside to the outside, linings, skirtings and coverings. We see great potential in expressing this order of elements and materials. Wooden window frames, windowsills in stone, wooden columns and beams, brick walls, gypsum plaster and so on. When the different tectonic elements and materials come together, they seem to create a collage of colours, textures, reflections and light.

And we are very interested in and inspired by the collage-like qualities of the building site – unfinished exposed structures, the visible layers of the walls being constructed, intermediate supporting structures, the colour of the scaffolding etc. The construction site very often expresses a spatial power that often is lost in the finished project. The porosity of interlinked spaces still opens to the outside.

So maybe it is about stop and rewind. Pausing time. Allowing the colours and materials of the construction site to colour the light and reveal the origin, weight and order of the space you are in. Material assemblages, colour collages.

Q: To continue the focus of colour and daylight: Do you use a special approach or a particular palette of colours in your projects?

Or does it differ from one project to the next?

A: When working with colour, we enjoy opening up the discussion by inviting artists or colour conservatists to collaborate and take part in creating a colour scheme for the project. On several occasions, we have, for example, collaborated with the Danish artist Malene Bach whose experimental approach to colour in architecture pushes the project further than we could have done ourselves.

We are often surprised and inspired by the boldness and radical use of colour in historic architecture or in the masterpieces of modern architecture. Think of the use of colour in Le Corbusier’s Villa La Roche in Paris. Yellow-coloured ceilings, turquoise furniture, radiators painted black. Or the coloured ceilings of Dom Hans van der Laans Benedictine monastery in Tomelilla, Sweden. Dusty blue, pink, green.

We are dreaming of creating a space under skylights with yellow-coloured glass and sun-coloured curtains that bathe the space in warm sunlight – with reference to Sir John Soane’s drawing room at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in Holborn, London.

Q: In your inspiring talk you refer to the works by James Turell and his approach to light and space. The work of James Turell has the German philosopher and phenomenologist, Gernot Böhme (4), described as “atmospheres” and furthermore as “the aesthetic felling of a space”.

Can you relate to that notion of atmosphere – and the urge to create a space which has a certain atmosphere?

A: In our talk, we mentioned James Turell’s work with light where he materialises light as an object of art. The ‘thingness of light’ as he calls it. We are very fascinated by this span in the work with light that goes from something invisible to something physical. I (Uffe) remember the special light in my grandparents’ house when sunbeams came in the windows and caught all the dust in the air (houses were much dustier back then). These beams of sun and dust were almost like solid physical lines that inhabited the space and changed it completely. It felt kind of magical and when I later discovered the work of Turell and his objectivisation of light is made total sense. Captivating light and utilising it to create beautiful, magical and atmospheric spaces is an important objective in architecture. And looking at the work of artists like Turell and Matta-Clark or thinking back on those magical memories of light in your life can help in achieving that objective.

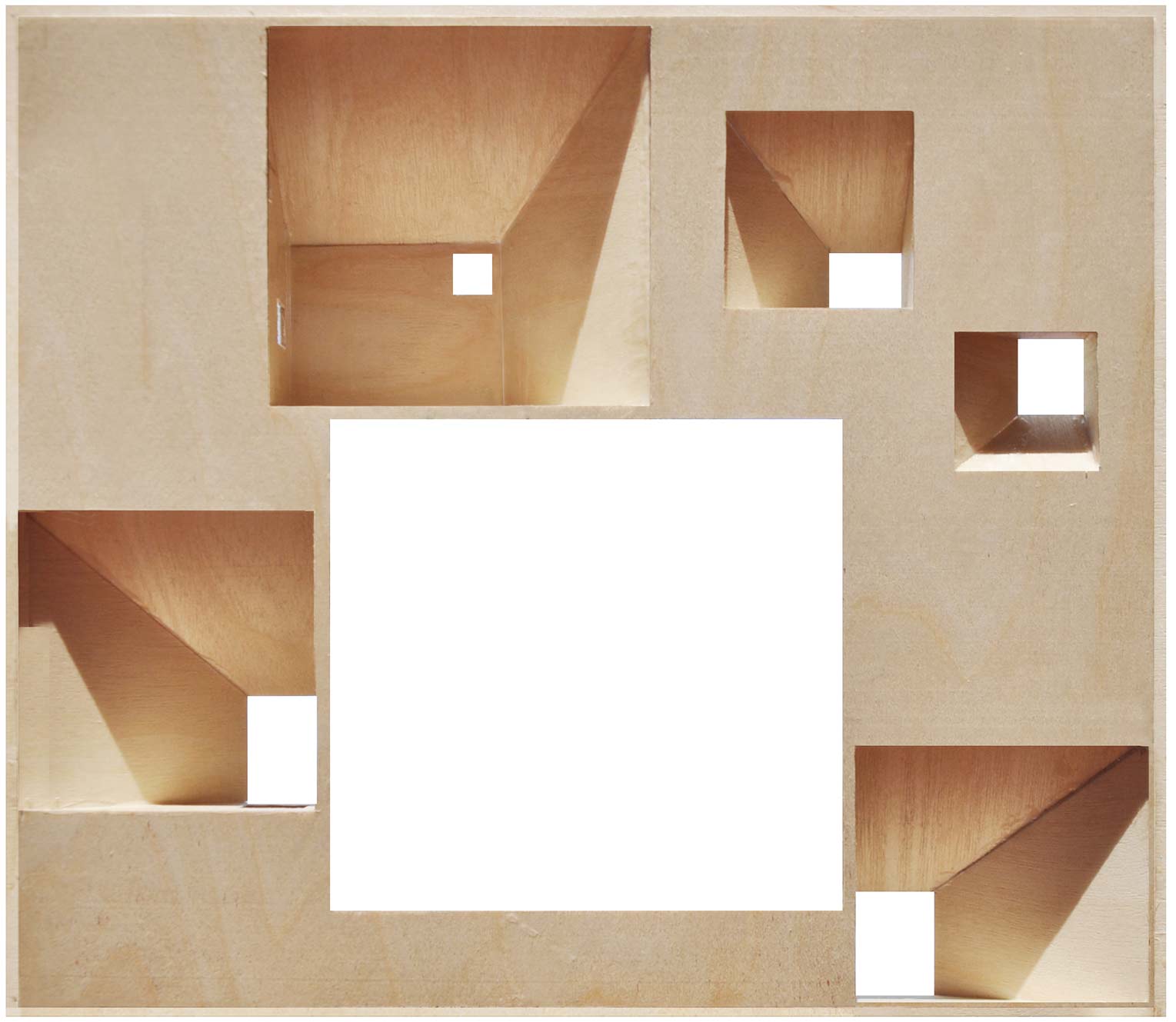

Q: In relation to the tools, we architects have available for examining and developing a space/a building, for example, physical models, digital models, drawings, renderings etc., what kind of role do you think your methods of using specific physical models in your work play in the effort to create atmospheres?

A: Juhani Pallasmaa has said that: “The final target of the architect is not the physical building, but its impact as a lived experience.” (5). This is, in our opinion, a very accurate and precise description of what should be ultimate goal for architecture. So how do we get there and how do we ensure that the quality of the end result is as high as possible.

In a battle between the physical and digital, we would always choose the physical option. Reading a book for example is a much richer experience with the physical book in your hands. You can feel the book, the weight, the texture of the cover, the quality of the paper. You can smell it. It is a physical object you can interact with. The same sensory qualities apply to the process of developing space and architecture in an analogue process. The fact that you can feel and inhabit the space with your body while drawing or building a model is simply crucial and an absolute necessity in a design process. The physical interaction with the project automatically generates many of the answers you need because you can sense the project and understand it with your body. Especially when we are talking about creating a specific atmosphere or light in projects, this physical interaction is vital and hugely advantageous because you can experience it physically. It is simply impossible to avoid that light will flow into your model and give you a pretty accurate impression of the daylight conditions.

All this said, we are not against the use of digital tools in the architectural process and we also use 3D models and CAD software extensively in the studio. But we still try to get it out of the computer and into the physical world as much as possible.

Q: In your work, you refer both to the arts, Gordon Matta Clark, James Turell etc., and architecture, especially the analysis of Sir John Soane’s museum in London is very central when you describe your sources of inspiration and wonder. Which other architects are your ‘heroes’? And are they placed in a Nordic tradition of architecture?

A: We draw inspiration from many different sources inside and outside the world of architecture. We both teach and our dialogue between the students and colleagues is an important source of inspiration. We also run an exhibition space in our office storefront, and the interaction with the people exhibiting and their work also inspire us. But inspiration is nothing in itself. In the words of Thomas Edison: “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration”. This is very true when applied to the creative process of making architecture where the basis of taking the right decisions comes from hard work and more hard work. So being critical and understanding the world of inspiration is also a crucial part of our practice.

Q: In the little handy book, “What is architecture”,(6)the Norwegian professor of architectural history and theory Mari Hvattum describes different turns in the architectural history, and defines “the turn” which is dominant now as “the perceptual turn”. What characterises the perceptual turn is that buildings are not only something to be looked at, they address all the senses: Smell, taste, movement and touch.

Can you see your approach to architecture as part of this new “Perceptual turn”?

A: We are familiar with Mari Hvattum through the exhibition project ‘Jävla Kritiker’ that we are both part of. But we are not familiar with the specific book, her thoughts behind the different turns in architectural theory and her reasoning when arguing that the ‘perceptual turn’ is the dominant direction in contemporary architecture. It would be wonderful if it were the case though. We would very much like to see a sensory awareness in architecture, but to be honest, it is easier to think of historical buildings that apply to all senses than contemporary examples. Take housing architecture, for example. The majority of housing projects that are built at the moment are of an unbelievably low architectural quality and can almost be categorised as an insult to human perception. Low-quality spaces, low-quality materials and no sense of light and place. Or public buildings for that matter. As a society we used to build city halls, school buildings, trains stations and other public buildings that were at the height of what we could produce architecturally, technically and functionally at the time. This is rarely the case anymore. To get back to the ‘Jävla Kritiker’ project, we recommend reading the text by Rasmus Wærn, which is the text our contribution to the exhibition responds to. In his text ‘En skola att bli stor I’ (A school to grow in), Rasmus describes a fantastic school building he calls ‘Dubbelgymnasiet’. A building full of atmosphere, surprises and spatial qualities. A building that is enriching to inhabit and which makes you grow as a human being. This building has somehow achieved to combine Hvattum’s sensory buildings with Pallasmaa’s goal of creating architecture that has a positive impact on the people inhabiting them.

This is maybe the future for architecture that we should hope for.

Notes:

1. Christian Norberg-Schulz: Nightlands. The MIT Press, 1996, p. 2

2. Christian Norberg-Schulz: Nightlands. The MIT Press, 1996, p. 9

3. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Goethe’s Colour Theory, Hernovs Forlag, Copenhagen 1988, p. 271

4. Gernot Boehme, Atmospheric Architectures, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2018

5. Michael Amundsen, Q&A with Juhani Pallasmaa on Architecture, Aesthetics of Atmospheres and the Passage of Time, Ambiances, 2018, p.3.

6. Mari Hvattum, ’Hva er arkitektur’, Universitetsforlaget, 2015, p. 25

Facts on Leth & Gori:

LETH & GORI is a Danish architectural studio founded in 2007 by architects Uffe Leth and Karsten Gori. The studio is specialising in site-specific construction projects of high architectural caliber.

The studio works with adaptations, alterations, conversions, modifications and transformations in projects ranging from new buildings to cultural heritage, with special focus on projects that give something back to the city. The studio is committed to creating projects with architectural longevity, characterised by simplicity, flexibility and distinctive details – big and small.

Uffe Leth and Karsten Gori both teach at the Royal Academy School of Architecture – Architecture, Design, Conservation in Copenhagen

Facts on Louise Grønlund:

Louise Grønlund is a Danish architect and assistant professor and The Royal Danish Academy – Architecture, Design, Conservation in Copenhagen. Her research and research-based teaching focus on the aesthetic qualities of daylight and on our perception of spaces. Especially the interplay between daylight and architecture and the appearances of daylight in interior spaces, surfaces, material and in colour. The research is bound in a qualitative and phenomenological approach and carried out through a combination of artistic research and academic work.