2024 - Exhibition in Sunlight

Category

Daylight in Buildings - Region 1: Western Europe

Students

Yihao Tong

Teacher

Marco Lucchini

School

Politecnico di Milano

Country

Italy

Download

Download project board

The Diocesan Museum of Milan has long been committed to meeting the new needs of civil society and the Church. One of the most urgent needs is the reconstruction of the fourth side of the second cloister of Sant’Eustorgio, which was destroyed during the bombings of the last world war. Unlike the other three sides, it has not yet undergone any restoration or renovation. The wartime demolitions left a cloister now serving as a museum with one side missing, a long facade along Corso di Porta Ticinese with a wide gap, and two bare gables that highlight the post-war incompleteness. Additionally, a park has grown over the bombed areas, replacing two demolished city blocks. This park now connects San Lorenzo and Sant’Eustorgio through open spaces, consolidating and historicizing a situation that contradicts the site’s history.

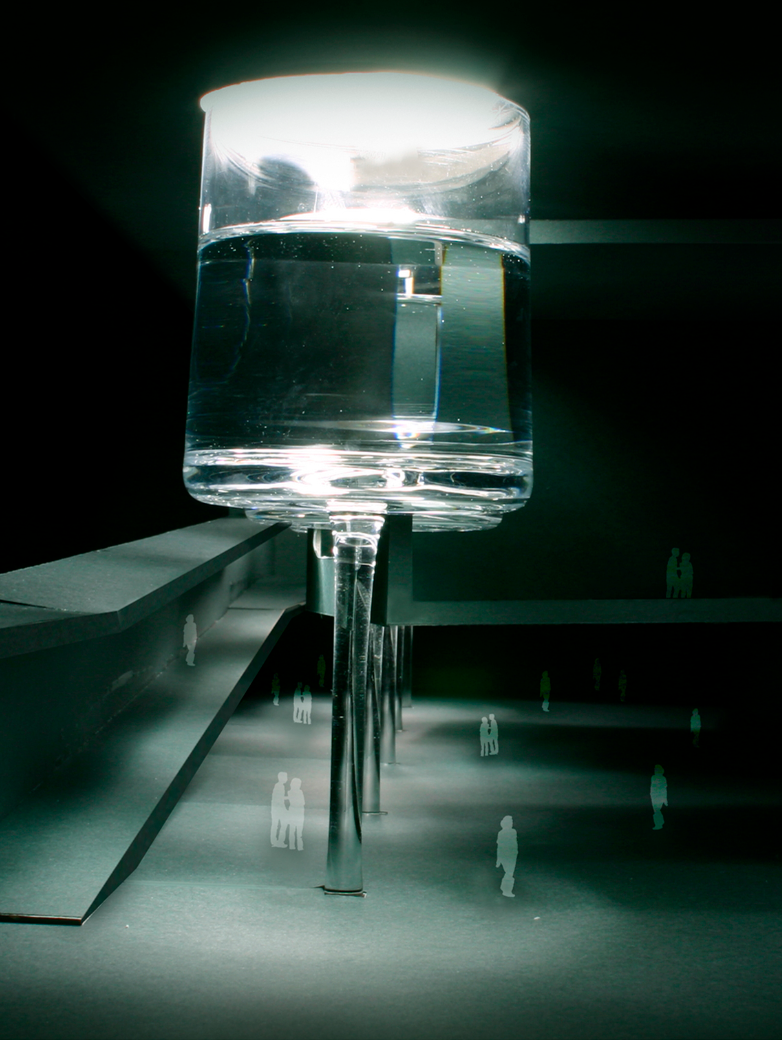

In a museum, exhibits react differently to sunlight. Sculptures can be exposed to sunlight, while oil paintings should not be directly exposed. Therefore, the new architecture can be designed with openings based on the requirements of the exhibits, reducing energy usage through design. Light emerges as a fundamental element of architecture, serving as the architect of time. Natural light not only illuminates space but also empowers the functions developed within it. Additionally, we can manipulate light within a space, introducing tension and evoking beauty.

In carefully measured and controlled amounts, tailored to achieve the desired effect, the sun’s solid light infiltrates a building through strategically drilled openings in the ceiling or walls. These openings may take the form of skylights situated in the uppermost horizontal plane, such as the plate roof, or windows positioned in the vertical plane within the walls. Solid light not only illuminates the architecturally designed space but also creates tension and harmony within it. Similar to how air passes through openings and strings, resonating within the chamber of a musical instrument to produce its distinct sound, solid light introduces spatial friction, endowing the space with its own unique ambiance.

When the Goths initially erected their stone cathedrals, the primary objective was to invite more light from heaven, quite literally from the sky. Light was intended to be the central element of Gothic architecture. The pursuit of more light aimed at imbuing these spaces with a heightened sense of divinity. These spaces became not only more vertical but also more “spiritual,” embodying a concept fervently pursued: the suspension of time.

Translucent light, often characterized by a more “whitish” hue, akin to a delicate cloud enveloping the space as if it had traversed through the sky. This majestic cloud, accentuated by a stone structure elevated to its maximum height, created a magnificent spectacle. However, with few exceptions, the innate horror vacui inherent in human nature prevailed, leading to the loss of that brilliant translucency. The result was an influx of more doctrine and a diminishing presence of light.

The museum also has radiant and translucent spaces, akin to a cloud penetrated by the sun’s solid rays of light – achieved to a degree where the processes unfolding within become tangible and visible. Analogous to the clarity differentiating light and shadows within the Pantheon of Rome, this novel space would distinctly exude translucency, unmistakably pierced by solid light. This essence encapsulates the concept of “piercing translucency.”

The resultant interior atmosphere will be one bathed in translucent light, creating an illusion of being enveloped within a cloud. When illuminated at night, the external appearance will resemble an inviting lantern. By day, the enigmatic radiance of natural reflected light will emanate from within, presenting an unparalleled spectacle.