FROM SUNRISE TO SUNSET,

FROM DESERT TO SEA,

A light journey in Morocco

Category

Daylight

Sunlight

Author

David Garcia

Photography

David Garcia

Date

01 JUN 2022

Source

Daylight & Architecture

Share

Copy

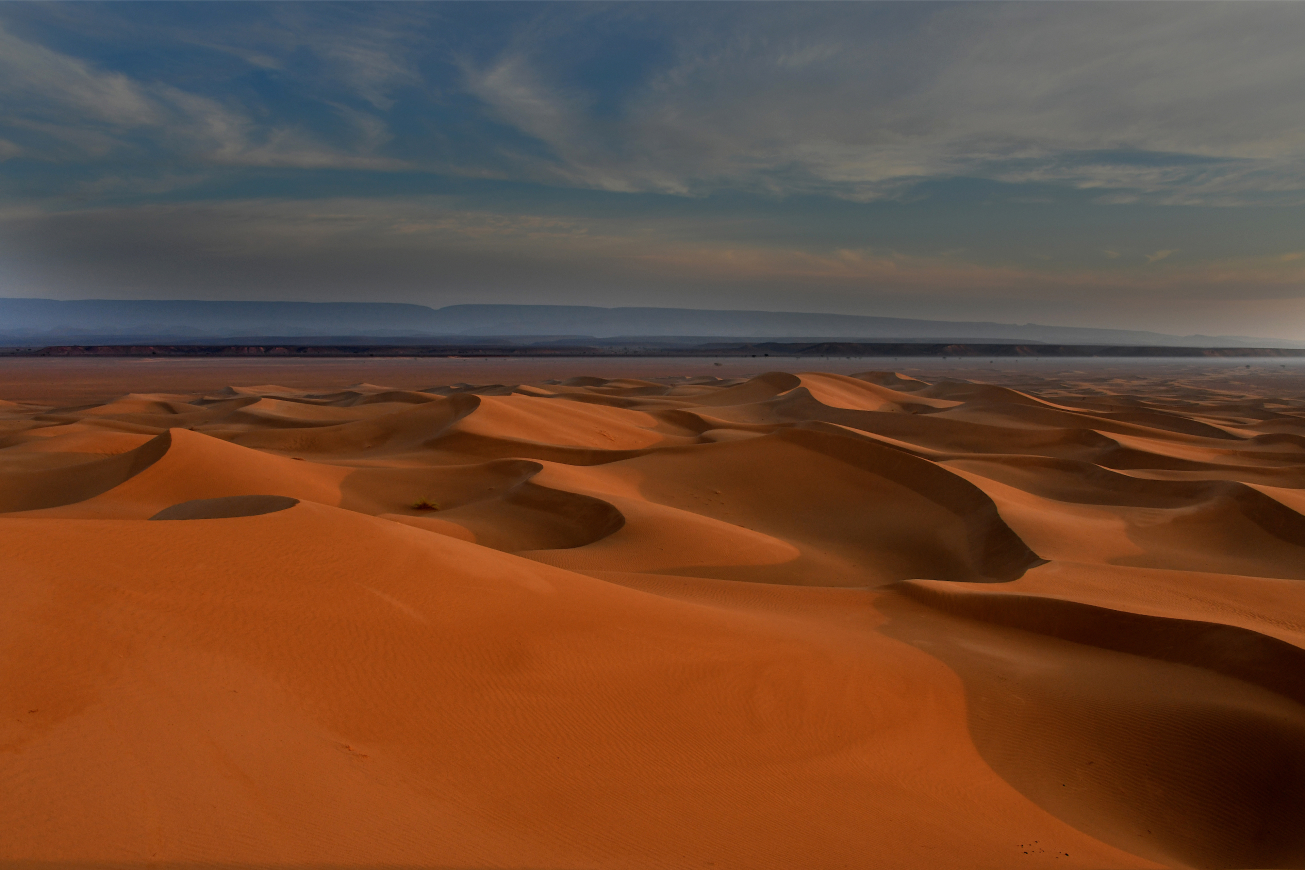

As I sit upon a tall desert dune in near darkness, sand humid with dew, the water droplets on the back of a Naib beetle glitter with the first signs of twilight. My gaze turns east. Low and distant horizontal clouds, as if giant louvers, break up the fast changing hues while the sky quickly transforms into lighter versions of the red, orange, blue and black that span from the horizon to the zenith. The bands of clouds give depth to the sky and the humidity in the air makes light thick and diffused.

Sun light, still low in the horizon, is travelling through a larger volume of atmosphere, allowing for more particle scatter. As I look at the distant sun disc, violet and blue spectrums are left behind, allowing for yellow, orange and red to break through; the Raleigh scattering effect.

The first “architecture” sunlight meets, is the atmosphere. It is the first physical structure, that shapes and tunes the sun rays. Sometimes subtle, other times blunt, its impact on how we perceive light is radical. As light reaches Earth, our atmosphere and the surface air, light is bounced, diffused and reflected accordingly, and at such levels that the impact is different from one atmospheric condition to another. It is the first environment light interacts with, and in turn it is greatly impacted by it.

In November of 2021, taking the opportunity of the yearly fieldwork of the architecture master program I lead at the Royal Danish Academy, I ventured into a journey defined by an investigation: To follow the light as a physical journey, from sunrise in the Sahara Desert to sunset in the Atlantic coast, and attempt to describe how this winter light, throughout the hours of the day and in different landscapes, meets architecture and our eyes.

The master course in Architecture and Extreme Environments I direct is a hyper-specific approach to design, through innovation and exploration. One of its many approaches is understanding a context holistically. Fascinated by how light and architecture interact I ventured into a phenomenological voyage to describe how context (atmosphere, geography, time of day, season…) impact the architectures I meet in our fieldwork destination for 2021, Morocco.

Where does light start? What happens before, when and after it reaches architecture? How does light engage with the built environment? These are crucial questions that have been explored for centuries and have defined many approaches to architecture. This essay is explorative but not universal. It follows a two-week desert and mountain crossing, where special attention was placed on natural light at a specific day, in a specific site, at a specific time. The photographs and this text attempt to convey this journey.

Back in the desert dune, seeing the Sun’s disc appearing in the horizon, I look down at the dunes below. Sharp shadows start to define the space three-dimensionally, making it almost scale-less, a frozen sea or a zoomed-in ripple. Between this majestic space I glimpse the tents. One, a piece of contemporary high-tech design, the other, a traditional Berber tent, made of goat hair and sheep wool, in hand-loom widths sown together. One exploding with light like a nylon lamp, heating up exponentially. The other, evaporating the morning dew with its dark color, and delicately controlling the amount of light allowed to enter. One built for ultralight minimal transport, is a shelter. The other, fine-tuned to the desert through its hundreds of years of evolution, is a home. Morning light slowly seeps in through the weave, as a gentle starry night, never blinding, and allowing just enough light to avoid overheating.

The northern region of the desert is lined with the Anti Atlas Mountain range. A series of rising topographies which from the south, announce the main Atlas Mountain range further north. The region, populated for centuries, consists of small settlements linked to riverbeds and gorges, which have allowed access to water and the consequent thriving of life. Much of the traditional constructions are made of mud bricks, rammed earth and mud cladding. The courtyard constructions, organically expanding in the landscape, are several stories tall, and often challenge the relationship between material and structural ambition, although the structures have often survived hundreds of years, proving their tectonic solidity. These are the Kasbahs.

Here, the terrain is not desert flat. It is dynamic and often steep. The mud color of the Kasbahs, fortified mud towns and citadels, often blend in with the varied topography, and light reflected off the landscape reveals or hides the architecture intermittently. As I admire Ait Ben Haddou, across it’s the Asif Ounila seasonal river, I need time to distinguish the landscape from the urban structure.

The second “architecture” light meets, is the landscape. Flat or mountainous, sea or land and everything in between, light is reflected by the large scale context. The geology of the territory, mud, granite, black basalt or greenish sandstone, “color” the light, redefining the architecture’s form and hues. If one is lucky to have cumulus clouds hovering at speed, the light theatre is overwhelming in its variation. Like a fast changing color filter on a photo set, the landscape and the town appear to change not only in color and shades, but also scale and depth seem to be constantly altered.

It is not only the formal structure of the village that is defined by light. Consequently, also the interior spaces are impacted by the nuanced rays, and how they are perceived inside the architecture. The structure’s materiality greatly shapes the already curated light, but the traces of its journey through atmosphere and landscape can still be perceived.

Light, like water, finds the smallest cracks, tinting the inner spaces of these ancient structures through courtyards and small openings.

The third element light meets, after its journey through atmosphere and landscape, is the built environment, architecture.

Higher in altitude and further north-west, now amongst the snow peaks of the Atlas, light varies again. This time, light struggles through the summits to reach the sheltered valleys below. Hidden in a defensive topography the Tinmal mosque, built in 1148, was the birthplace of the Almohad movement, which overtook the Almoravids in the mid 12th century, in territory, culture and also architectural style. As I enter this space, one of the first examples of this formal style still surviving amongst the high mountain ranges, the vaults overtake the sky, and a sophisticated play of shapes and light unfolds in front to me.

My eyes, the final receptors of light through its many ricochets and travels, are protected from the crisp noon sun, by the arches and Muqarnas, slowly breaking down the harsh light, through decorative three-dimensional detailing. The exquisite geometrical endless squinching which transitions the arch and the dome from circle to square, is not only a formal transformation, but a subtle light diffuser that skews the harsh corner, by exploding geometries and light reflections at the same time. These gestures, the Muqarnas, are eastern in origin and have traveled west through the centuries, to be reinterpreted at every turn.

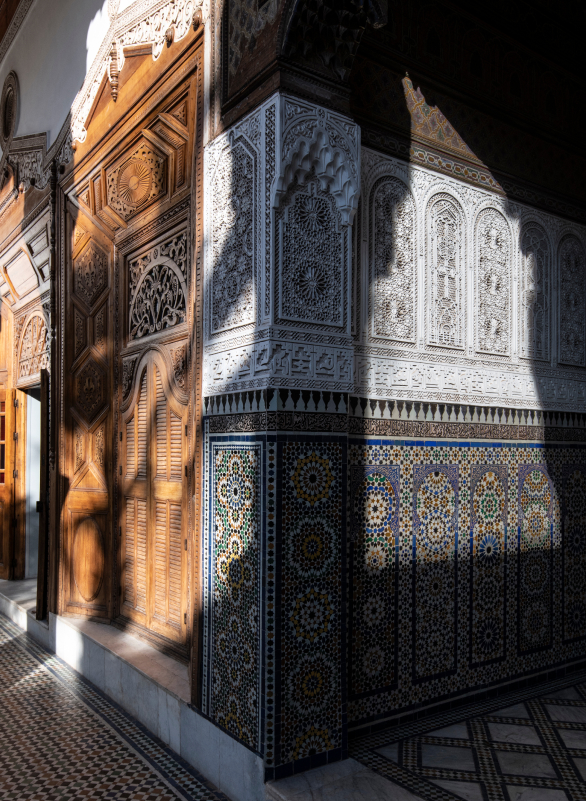

Now early afternoon, and on the north side of the Atlas, shelter from the harsh light and heat take on a refined form in Marrakesh. The Dar el Bacha, built in the early 1900s for the pasha of Marrakech, is a refined collection of architectural solutions. Now a restored palace it is a collage of Zellij, geometric mosaic tiles of many colors, combined with carved stucco, Muqarnas carved in wood and cedar ceiling decorations.

A fine example of how architecture can curate light through massing, surface color and material, manifested as a catalogue of spatial expressions in constant dialogue. High rooms allow for small ceiling light shafts to bounce and give just enough light without heating the space, atomizing the blunt force of the sun. Just as nuanced is the courtyard. Nature and artifice overlap. The materiality of the surfaces evolves from hard and cold materials at low level, to soft and warm higher up in the niches carved out of the atrium’s periphery. From marble to tiles, from plaster to cedar wood, not only do these materials react differently to temperature, but also to light. As a curated lens, only in winter do the white plaster wall surfaces receive light, reflecting it downwards and making the mosaic Zellij explode with color. The warm cedar ceilings, a chromatic warm contrast, as are the large wooden doors which mark the entrances to chambers.

The courtyard greenery and its reflection of light is in constant dialogue with the architecture which frame the trees. At eye level, the division of trunk and branches is reflected in the walls where mosaic ends and plaster work starts. An inverted symmetry which balances the way light and color reaches our eyes.

As I reach the Atlantic Ocean, the western tail of the Atlas mountains dives into the sea. Villages close to the coast often had a fishing harbor which with time itself evolved into a village, mainly curating for tourists. Imsouane, one of many examples, is defined by the harbor and its fishing activities but the recent growth of visitors has created a different type of architecture. Tailored to host, but not to house, it is instant and disregarding of how light has been curated in the region for centuries. As the sun sets, the reddish glows again tint the landscape, a symmetry of the desert sunrise, but radically different in its light. Here, it bounces off the sea, a blinding shimmering mirror, which, like mountains in motion, change light constantly. The reflection and the direct rays meet and color cliffs and surrounding topographies. These tones fall upon the village, although this time received by an architecture full of missed opportunities. Constructions for consumption, fruit of economic necessity, have disregarded many possibilities.

My eyes, the final receptors of this journey of light, ponder on this endless cycle of day and seasons, and the way architecture at its best has been inspired by the first spaces light meets: the sky and the landscape.