FROM STONE TO LIGHT A photographic journey in Rajasthani Architecture

Category

Daylight & Architecture

Daylight in buildings

Research and Innovation

Author

David Garcia

Photography

David Garcia

Date

February 2025

Source

Daylight & Architecture

Share

Copy

Outside Jaisalmer Fort, 8 am.

As I walk through the streets towards the elevated fortress of Jaisalmer, the dry wind from the Thar Desert burns the right side of my face, while my left side is scorched by the sun. While I consider which is hotter, I cover my eyes from the blinding sun and remind myself this is exactly the challenge architecture in desert regions aims to mitigate.

The experience is enhanced by the thick, yellow, cloud of dust, filling the air. Everything is yellow. The sky, the ground, my clothes and my hands. Sharp sounds ring the streets, and I follow the rhythm picked up by my ears. Meandering through slabs of yellow stone, like toppled dominoes for giants, I see a group of workers in a courtyard surrounding a giant saw slicing sandstone blocks as large as cars. Hammer and chisel in hand, the workers ping and splinter the sandstone with metronome precision. The slab sings like an instrument losing weight with each stroke, as intricate geometric patterns are revealed with each hit. Every ten strokes or so, the worker exhales through the hollow hammer handle to remove debris from his carving. With each blow, yellow dust flies away from the sandstone slab, falling upon our faces, like yellow snow.

Here and for centuries, Jaisalmer’s sandstone blocks have been carved, and the latticed panels have been hollowed – one of many sites where locals have exploited this material and the ways it could tame the burning heat and the blinding light of the Rajasthani deserts. The work repeats everywhere I look, beyond the street, across the neighbourhood, endless orchestras of sandstone transformations, from mass to air, from stone to light.

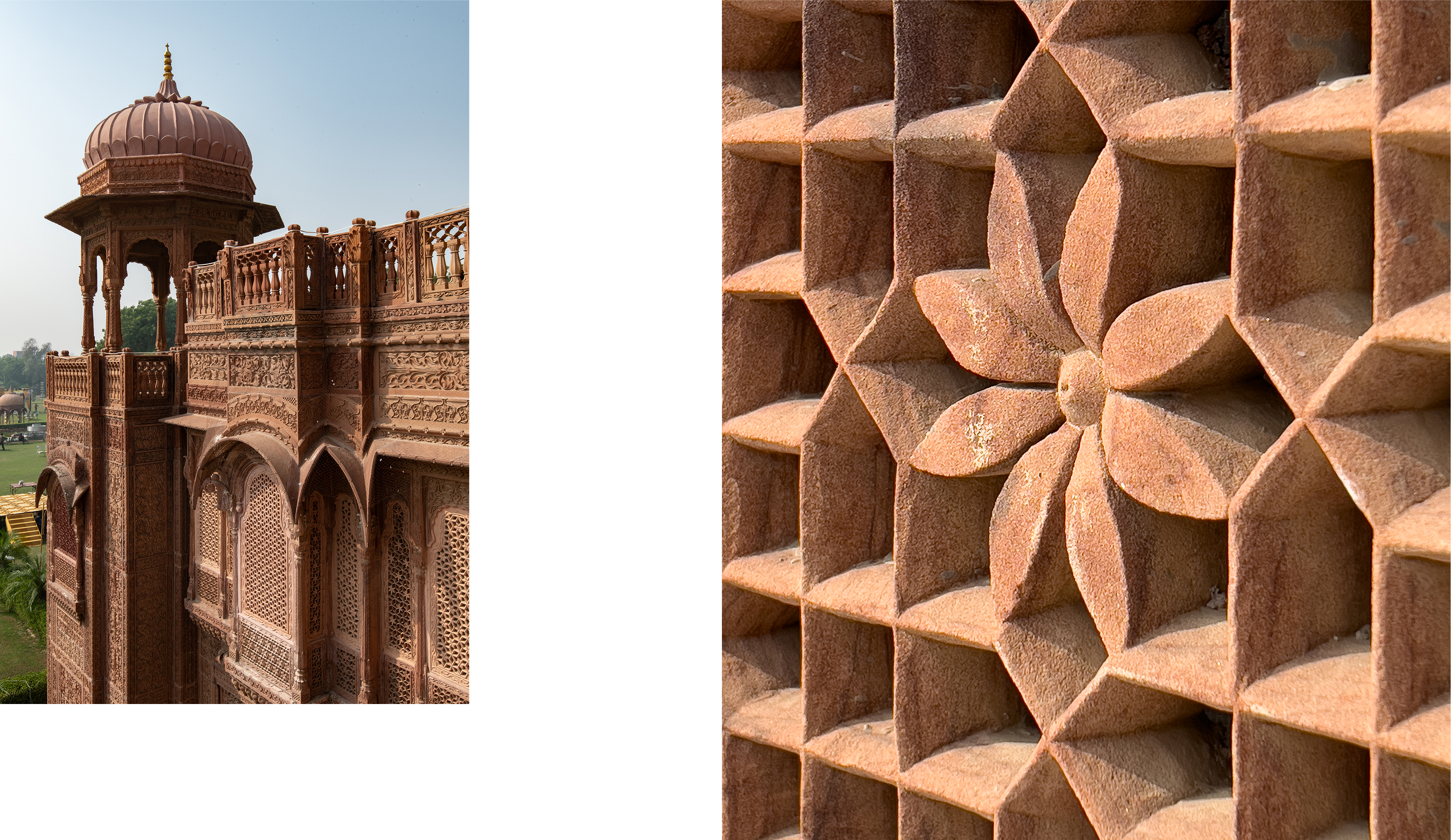

Indo-Islamic Architecture spread through the northwest of India and reached Rajasthan in the 16th century, merging with local building traditions and enhancing many solutions towards climate comfort. In Jaisalmer, as in many ancient cities in Rajasthan, the overriding material is sandstone. Structure and facades, floors and decorations, roofs and stairs, and often hinged eaves and small doors, are all made and carved from the local sandstone. Given the dry and arid nature of this region, the presence of the Thar Desert, where temperatures easily reach above 45 degrees Celsius during the summer and solar radiation is extreme due to clear skies and almost no rain, local architecture has evolved to mitigate solar impact, while exploring ways to exploit natural light.

Building orientation is a universal first approach in mitigating solar irradiation. The surrounding building mass offers shade, specially at the lower floors. The horizontal rays from morning and afternoon sun are not as strong as the high radiation of the almost vertical sun at summer noon. As such, facades have different treatments according to orientation and internally inhabit different functions. It is the singular use of facade solutions which make the architecture of this period a formally rich and functional effective vocabulary in light control and thermal comfort.

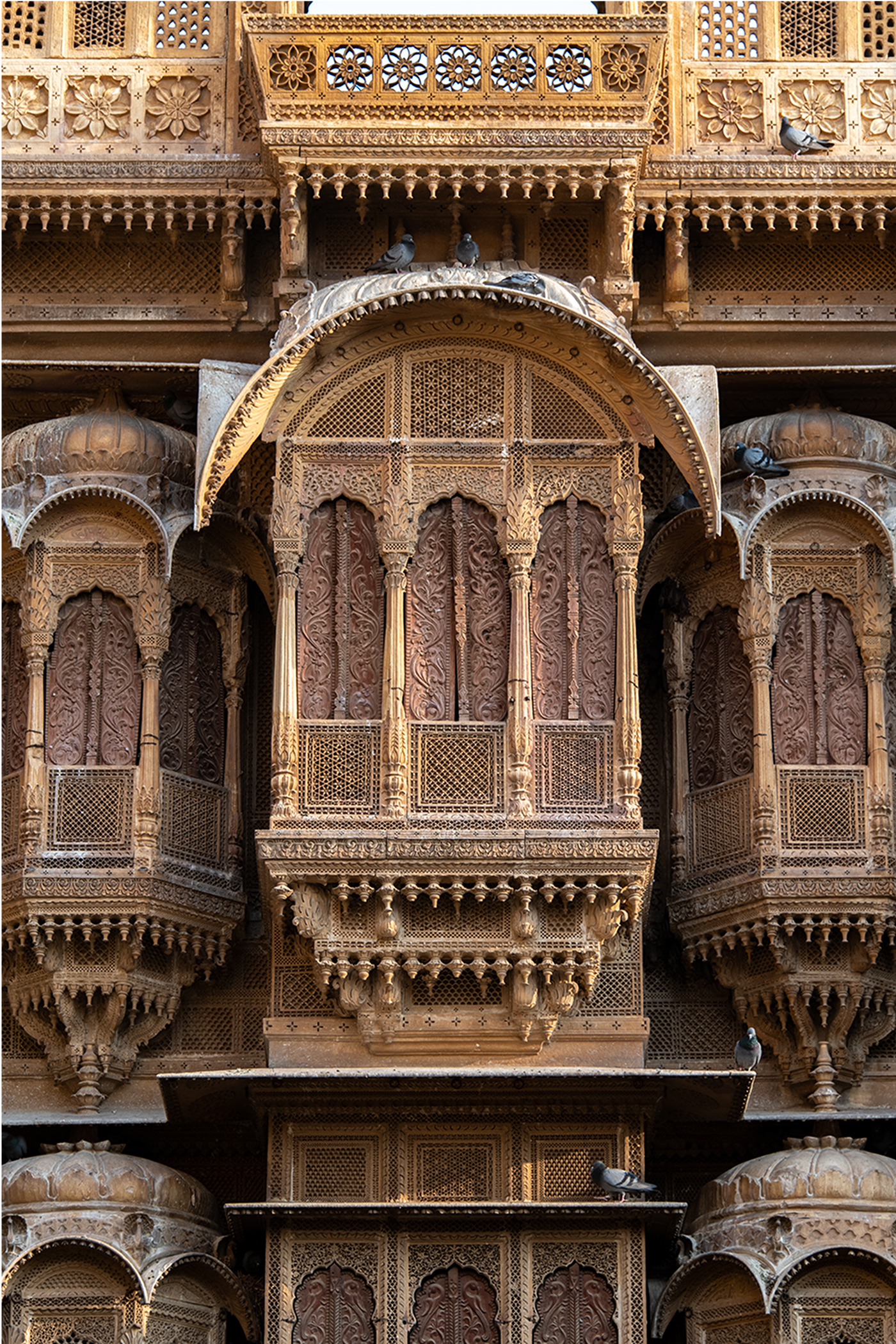

The Royal Palace in Jaisalmer Fort or Raj Mahal is a fascinating example. The seat of the Maharaja, built in stages between the 16th and 18th century, cradles one of the main gates of the fort and faces one of the main squares.

Its base, almost a socle, partly due to defence and privacy, stands bare and void of any shading strategies due to the sun seldom reaching the ground level. Neighbouring buildings cast shadows onto the main square and the first floors of the palace, making shading solutions unnecessary.

In other examples, like the Kothari’s Patwon Ki Haveli just outside the fort, where solar radiation reaches the ground floor, shading solutions immediately start at street level. In these cases, the horizontality of the street meets the verticality of the facade with gestures for social interaction where shade and light are nuanced to allow for rest, improvised meetings and curated entrances.

The gradual journey from blinding outdoor light to cooling indoor darkness is mediated through a series of local architectural solutions. Chhajjas, or overhanging eaves forming protruding planes at an angle, are a first barrier against the summer sun. These flat undecorated thin panels of sandstone remind us of extended roofings to shelter facades from dense monsoon rains in other regions of the world. Instead, here they block the pouring sun, and shelter canopies and balconies from its heat. Blunt and less sophisticated, they draw a precise geometric line in facades. The reflecting sun-lit surface and the cast shadow below the Chhajjas are recurrent elements identifying each floor of a building. They work in coordination with patterns and carvings, Jharokhas or stone window projections, and Jaali or perforated and latticed stone screens, to define the rich formal characteristics of the architecture in the region.

Patterns in facades, carved as bas-reliefs, are extensively used in Rajasthan and not only as decorative gestures. With the sun reaching high altitudes in the sky, small protrusions and reliefs in south facing facades create a myriad of small shadows, protecting the sandstone from the sun and the corresponding heat. The play of light and shade, rhythms with dark and light, are exceptionally explored as an aesthetic and functional palette to reaching sophisticated levels of detail. From geometrical patterns to floral rhythms, they become richer and denser toward the higher levels of the buildings, where architecture is more exposed to solar radiation and less shaded from surrounding structures.

Jaisalmer, Raj Mahal, 11 am.

I stare at the golden facade of the Raj Mahal. As my gaze rises, the palace seems to disappear into thin air, slowly vaporising from floor to floor, from massive pedestal to ever lighter filigree, as if eaten away by piercing sun rays.

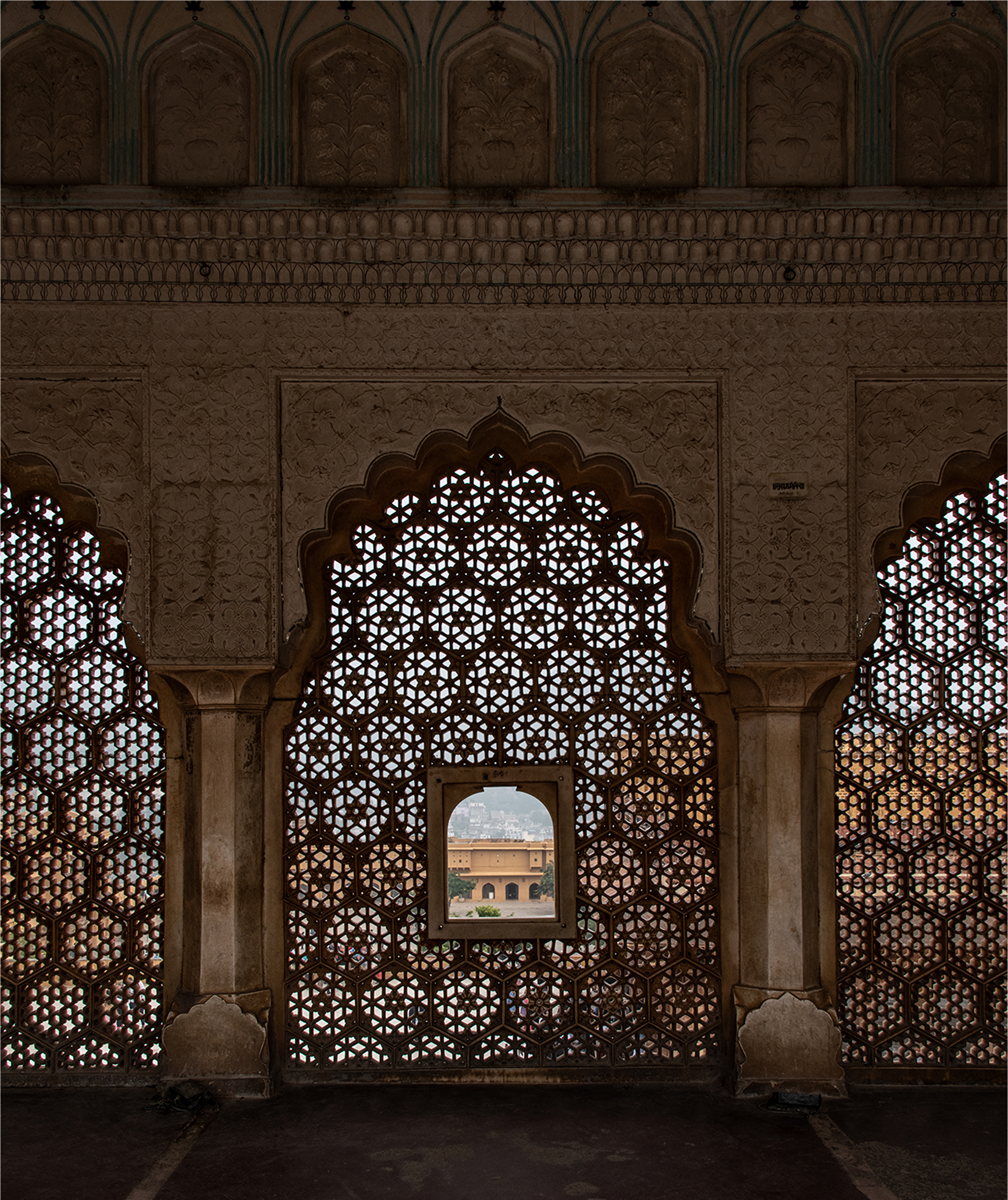

I have been given access to all the rooms of the palace by the Maharaja. A key keeper opens room after room, some, he says, not opened in 30 years. In our journey, we fall through the floors of two spaces, dust and stone creating shafts of light through the small facade openings. I imagine what the palace must be like under a sandstorm. Reaching the higher floors, I crawl on my knees along the balconies, over three hundred years old, cantilevering over a metre on the south facade and made solely of sandstone slabs, so thin and intricately carved, I fear it will all crumble under my weight. The gentle wind filtering through the perforated panels or Jaalis, calm my fears with a cooling breeze. I dare peer out of the floating windows within latticed walls. I can see without being seen and the market sounds of the Dusserha Chowk square invade my senses. I retreat to the shelter behind the Jaali, as hundreds of small holes become funnels, magically merging sun beams and wind in such a way that light becomes moving air.

The strong glare from the noon rays is severely reduced as I step back into the room preceding the balcony, the coolness is intensified by glassed tiles in blue tones, and light only reaches this space from the Jaalis in the balconies, which glow as if the distant facade has become a soft lamp of filtered sun. I rest.

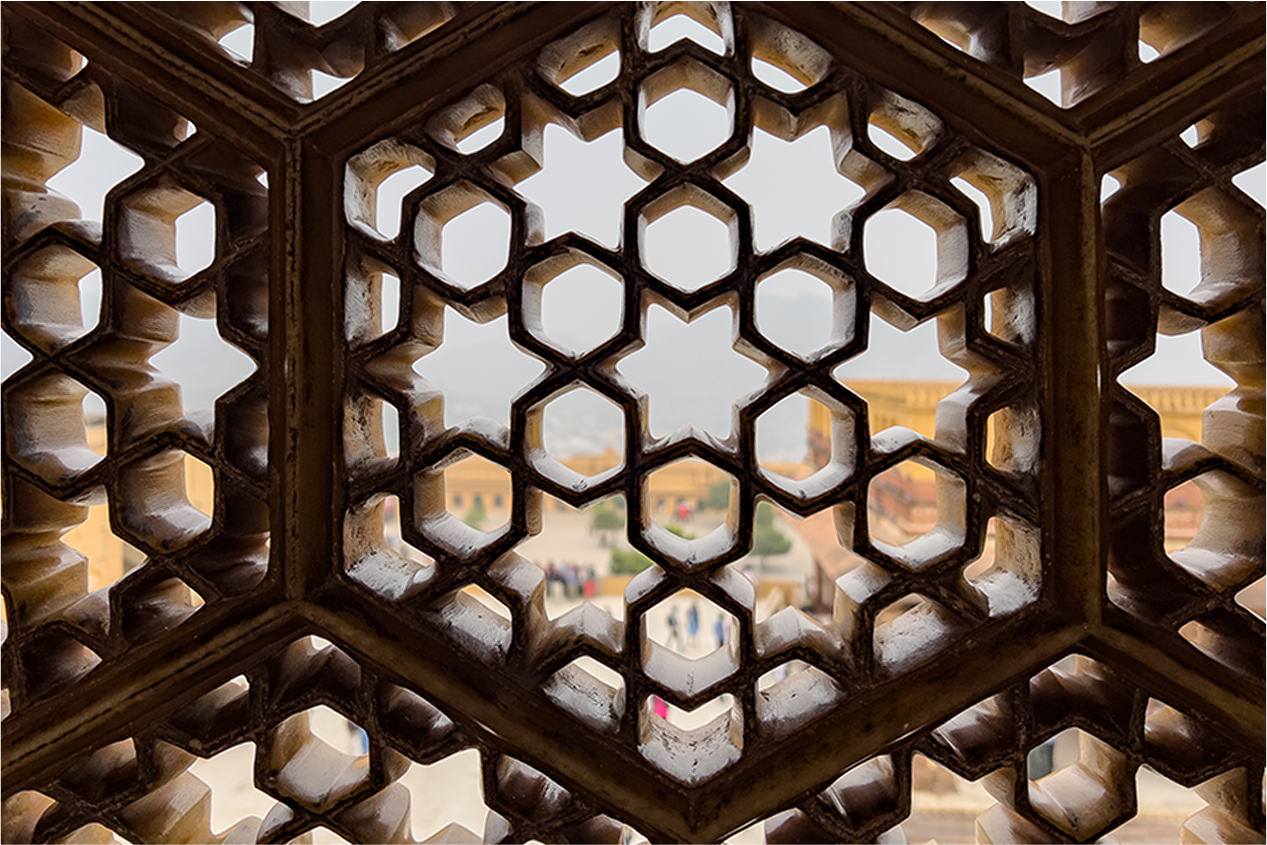

Jaalis are extensively used in the region and throughout the Asian continent, but the combination of sandstone as a sole building material and the interplay of solutions to combat and control light define much of Rajasthani architecture. Supporting a social and cultural need to see outside but not be seen, especially in women’s quarters of the time, the Jaali was (and is) used as both a social filter and a privacy screen. Often, the Jaali becomes a frame for a decorated miniscule window with an opaque stone frame of its own, appearing to float in space, among a thin lattice of hollowed stonework. These panels covering extruded balconies, as well as on facades, tame the strong rays before they enter interior spaces, much resembling the pattern of tree leaves and their light filtering qualities. To capitalize as much as possible on the remaining light allowed inside the building, walls and materials are selected accordingly. In the more austere spaces, whitewash allows low levels of light to brighten the space, and small latticed openings stamp a room with their moving light patterns.

Other more elaborate solutions, include tiles and carefully selected shades of paint and decoration, to gradually control the light levels experienced indoors. The more ostentatious solutions, as seen in the Sheesh Mahal in the Amber Fort in Jaipur, include tiles made of mirrors, creating a glittering ceiling, almost resembling raindrops lit up by morning sunlight or shimmering moonlight, as the local name for these tiles, Chandni, suggest.

This balance between light control and cooling function is exploited at its maximum in the roof pavilions. Here, social events and daily living can co-exist with the high temperatures due to the best exposure to wind, and the enhancing cooling effects through the perforations of the Jaali. Normally covered by a curved rooftop or Bangaldar, they crown palaces and Havelis, signalling the more luxurious of outdoor/indoor spaces.

There is no doubt that the poetics of light in space was and is a very conscious element in architectural design in Rajasthan. The ambition of making the lightest possible expression out of the heaviness of sandstone, was paralleled by the desire to control the desert light, and the vocabulary of qualities achieved always manages to “move” the user to a different spatial realm than the harsh exterior offers.

Jaisalmer Fort, 5 pm

It is the afternoon, and after five hours of meandering through most of the spaces in this palace, from its basements in the noon heat, to moments of comfort and calming light, I finally reach the rooftop. The key master who patiently has opened every room for my photographic project, shakes the ring with hundreds of keys at me, and smiles. He also enjoys the solace of the end of this journey, and as we sit amidst the cooling tiles, we look out through the Jaalis to the golden glow of the sandstone rooftops of Jaisalmer.

There is no roof cover where we sit, and only sheltered niches where the royalty would rest surround a miniscule courtyard. The sun is low in the horizon and the rays flow straight through the Jaali. It draws patterns on our faces, and we become drawings of a geometry that will again be carved from stone and in turn give form to light.

REFERENCES

Aastha Yadav, Dr.Anjaneya Sharma (2023) Vernacular Architecture Of Jaisalmer

Sofia, M. Manisha (2021) Indigenous Architecture of Havelis in Rajasthan

Vinod Gupta (2014) Natural Cooling Systems of Jaisalmer

Jane Matthews (2020) Natural Cooling Systems of Jaisalmer