Don't fight climate, use it

Category

Daylight

Daylight & Architecture

Research and Innovation

Uncategorized

Author

Florencia Collo

Source

Daylight and Architecture

Share

Copy

TOWARDS AN ARCHITECTURE THAT CAN ONCE AGAIN BECOME A SPACE OF ACTIVE PLEASURE, NOT MERE CONSUMPTION

Our work methodology and ethos

We founded Atmos Lab as an environmental design practice committed to working with climate. Our overriding aim is to design comfort (visual and thermal) into the building itself rather than forcing it through artificial means. Put differently, we prioritise passive, low-energy strategies that work with the climate and with what there is – leveraging sun, wind, and built form – to avoid resorting to machinery or electricity. This approach draws from time-tested wisdom, as before the emergence of air conditioning, all buildings achieved comfortable conditions through orientation, form, adaptive elements, and occupant engagement. At least, they reached the most possible comfortable conditions that the environment allowed with architectural intelligence. This principle emerged from our shared background in Sustainable Environmental Design at the Architectural Association (AA) in London, where all three of us, the founding partners, Rafael Alonso Candau, Olivier Dambron and I studied under the direction of Simos Yannas.

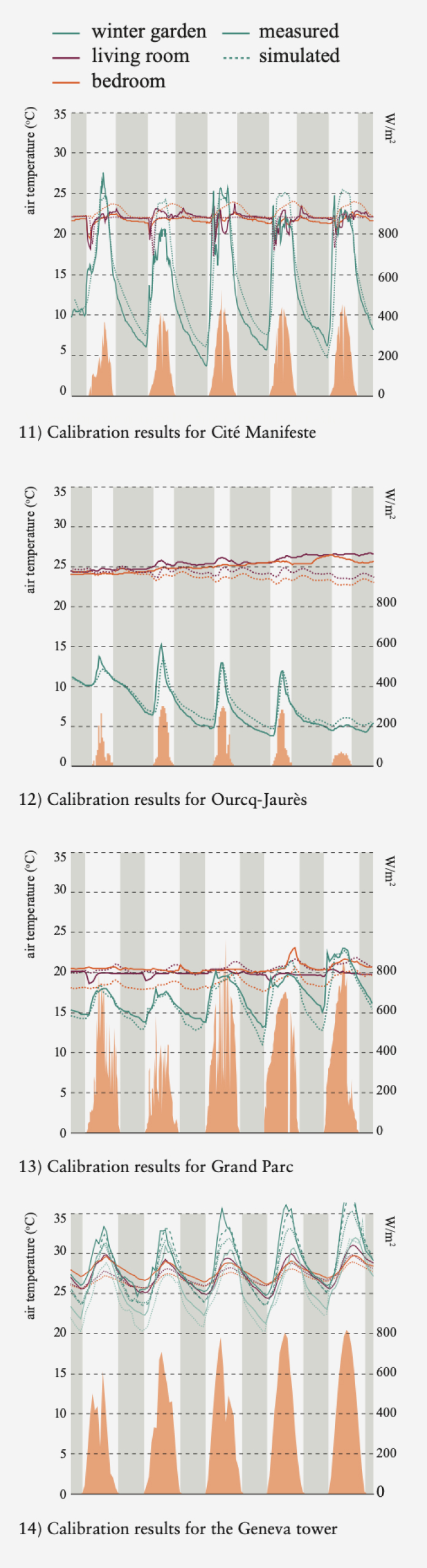

Our methodology is research-driven and data-focused. Each project starts by understanding local climate conditions, traditional common practice and user needs. In the case of renovations, we measure real-world conditions – temperature, humidity, indoor air quality – then calibrate a digital model (“digital twin”) of the building. This ensures that our simulations reflect actual performance. Once the model is validated, we explore program changes, behaviour changes or architectural changes (such as altering facades or reducing airtightness) to see which interventions yield the best results with minimal energy. By the time we propose solutions, they are backed by both real measurements and predictive modelling.

Working with precision and with the latest standards allows more flexibility to take decisions, as precision avoids generic solutions. Rather than seeing comfort as a narrow band mechanically enforced at all hours, we acknowledge human capacity to adapt; we open or close windows, adjust how we dress, or move into shady corners. To be able to account for all these elements in the models, allows us to work with all the complexities of real life and find solutions elsewhere that are not machinery. Indeed, big transformations often hinge on small changes – like lowering a heating setpoint by a couple of degrees or letting fresh air flush through a building at night. These strategies may seem simple, yet they significantly reduce reliance on mechanical conditioning.

We understand architecture not as a sealed container but as a dynamic interface with the surrounding environment. By bridging scientific rigour and design intuition, we work toward buildings that breathe, welcome daylight, introduce intermediate spaces, and allow occupants to feel engaged with shifting seasons.

It’s Nice Today: On Climate, Comfort and Pleasure

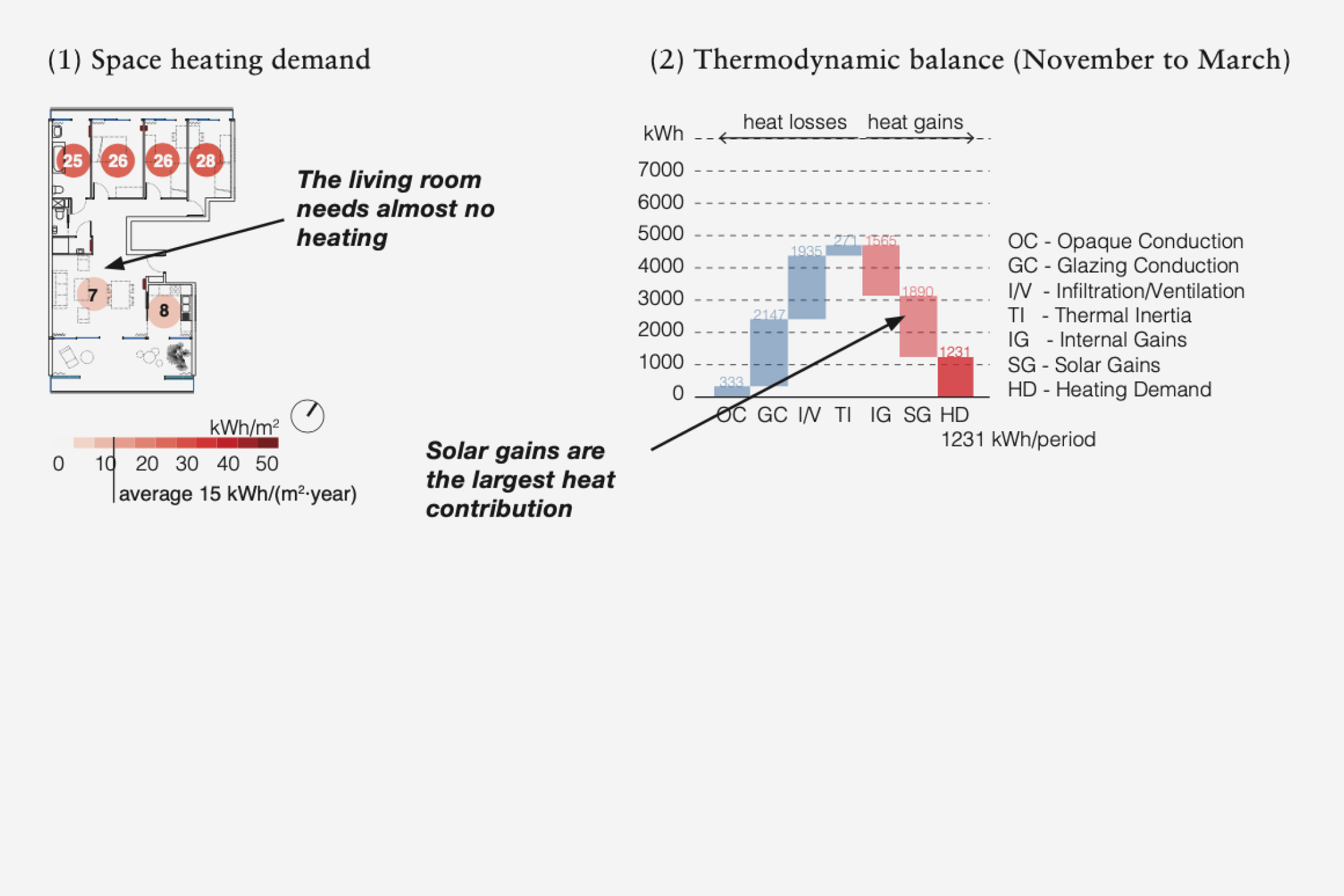

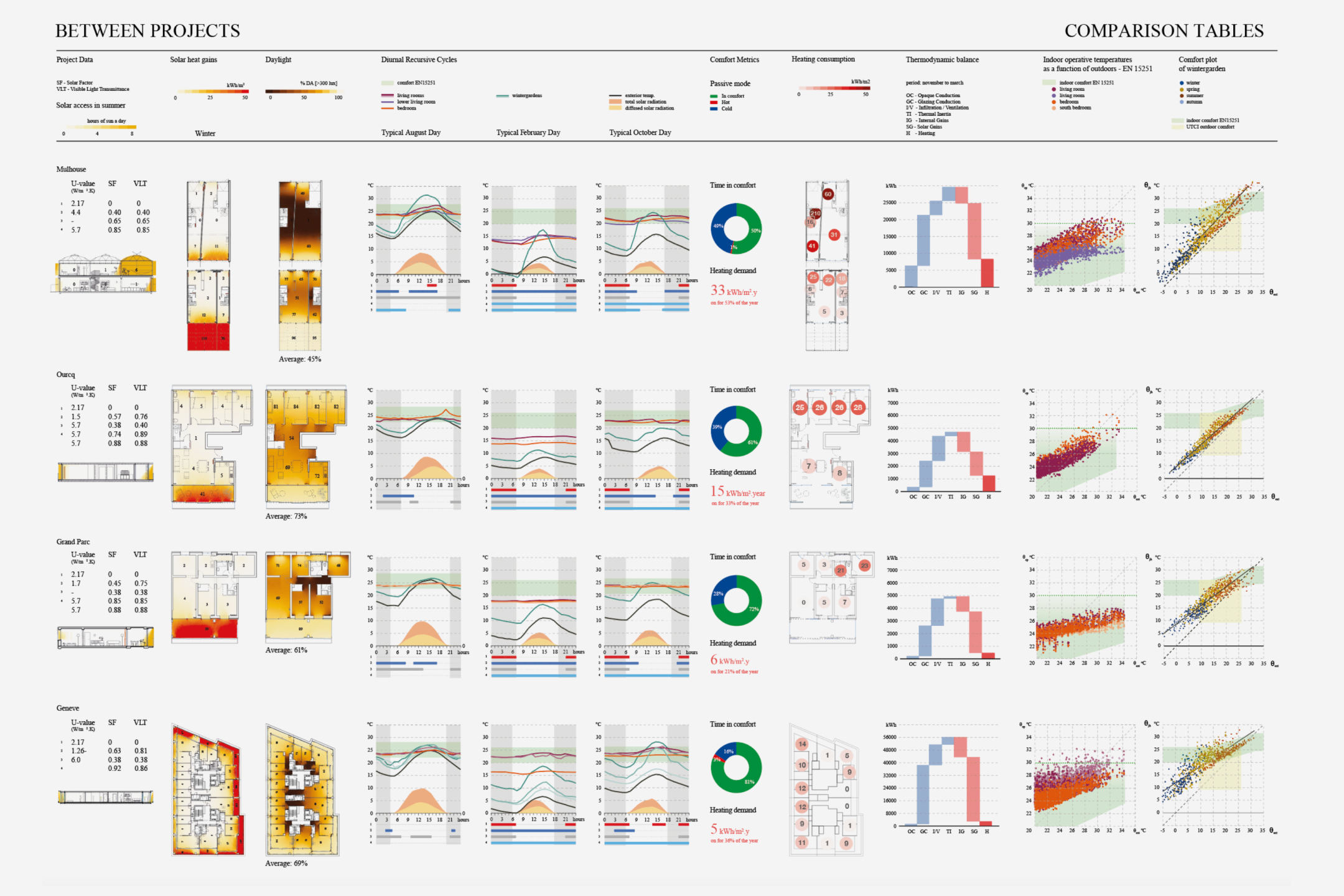

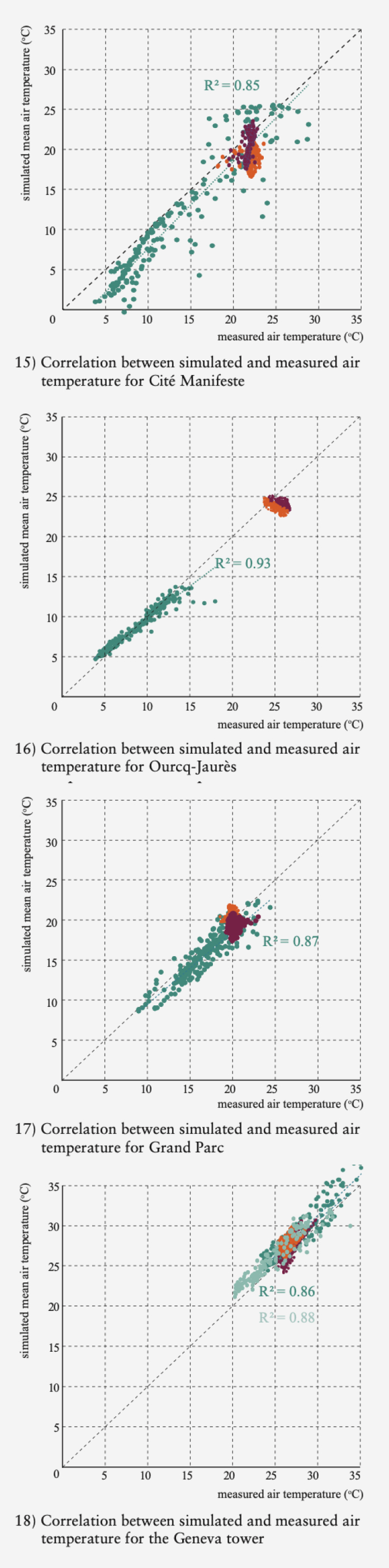

It’s Nice Today: On Climate, Comfort and Pleasure, a recently published book, co-authored with Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, was issued out of a long research project that spanned six years about their work. The book displays an in-depth study of their winter garden system and all the architect’s thinking behind the designs. This format allowed us to close the loop between design intentions, reality, occupant feedback, and design outcomes for current and future collaborations. The objective was to show the benefits of their bioclimatic features, and for this, four projects built between 2005 and 2020 – new constructions or transformations of existing structures – were revisited.

“The first step in the research was fieldwork, with temperature and humidity measurements and interviews with the occupants. Then computer models were created and calibrated. To maximise their accuracy, we used the actual performance of the building as determined by our measurements as a reference point. The aim was to mimic the actual measured temperature by adjusting building properties in the models that are often invisible and cannot be determined in advance or otherwise (such as air infiltration, air exchange, thermal inertia, and internal heat gains). For each case study, we analysed climate, solar incidence, potential for air movement, daylight levels, and thermal behaviour; together with comparisons of alternative scenarios. First simulations were carried out in “free-running” mode, meaning without the use of heating or cooling, to understand the natural conditions the building provides by itself. Then, the residual energy demand was studied.”

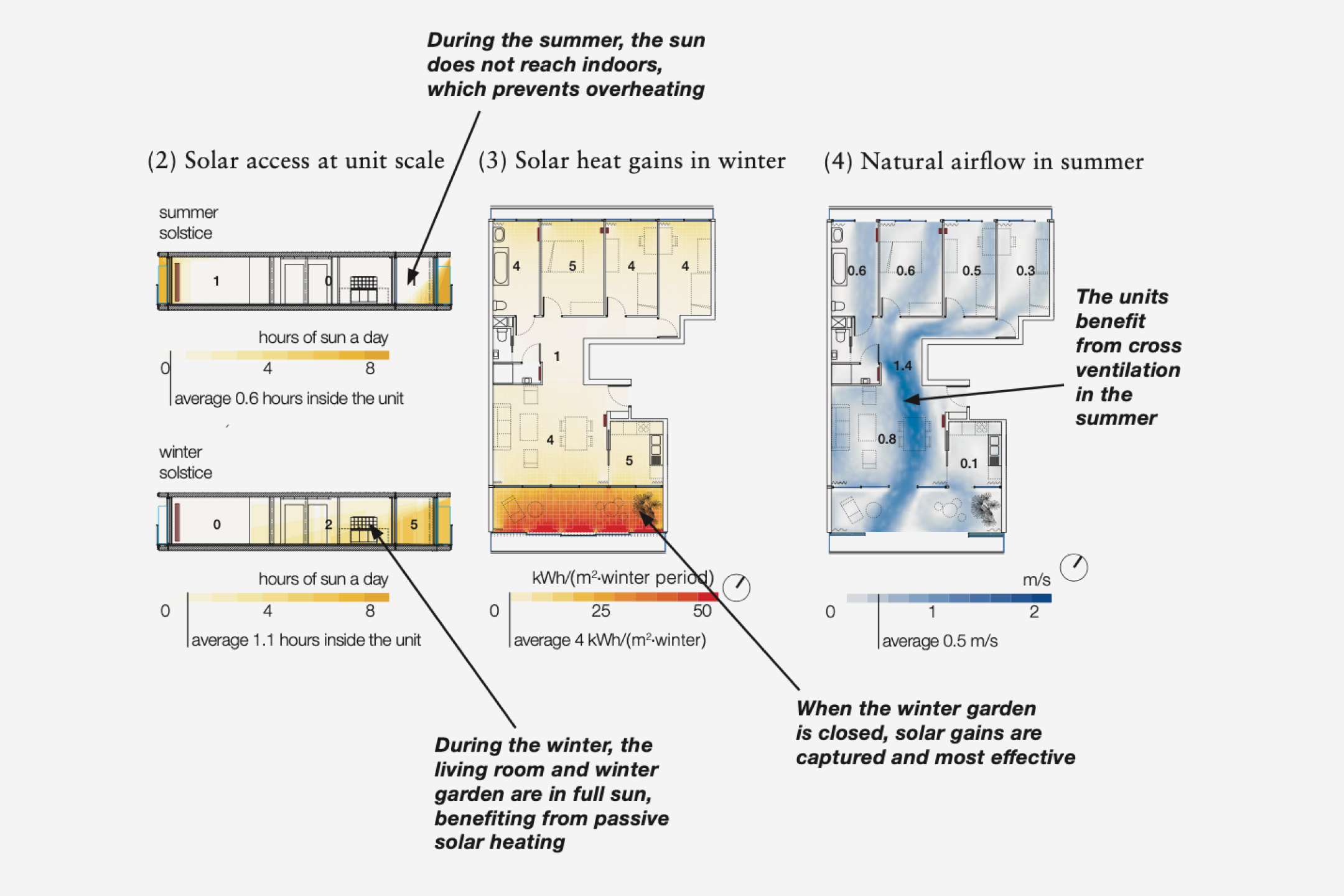

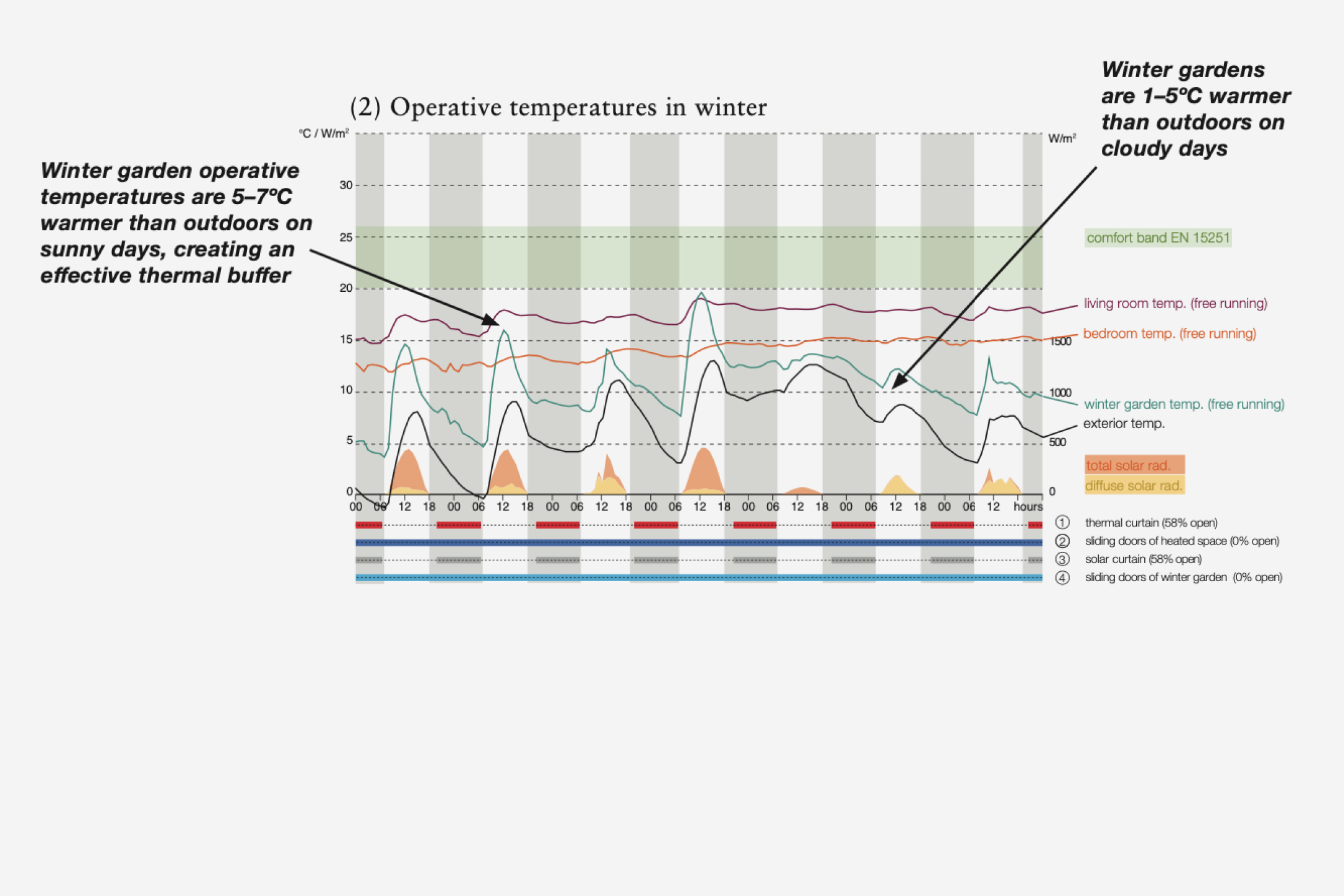

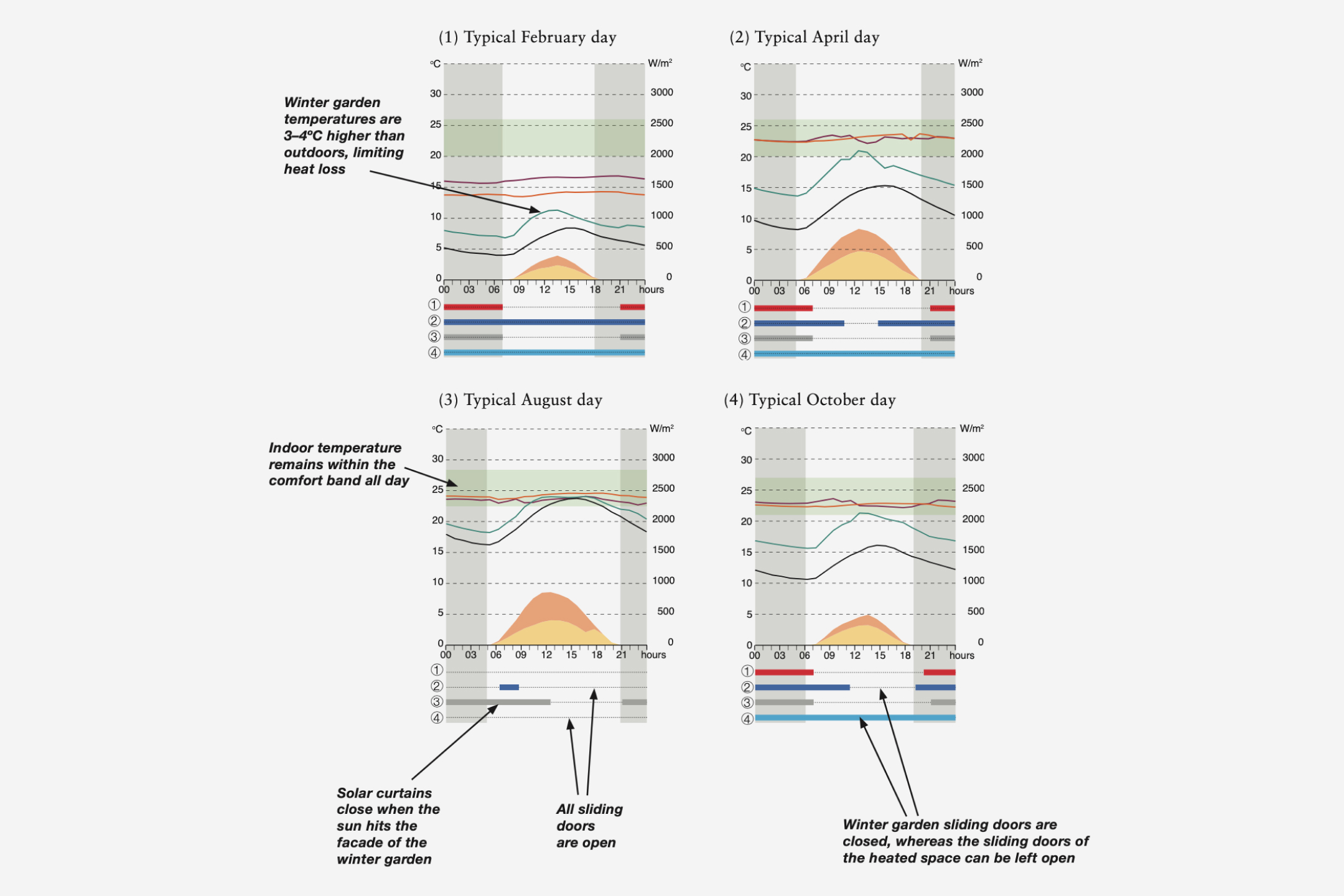

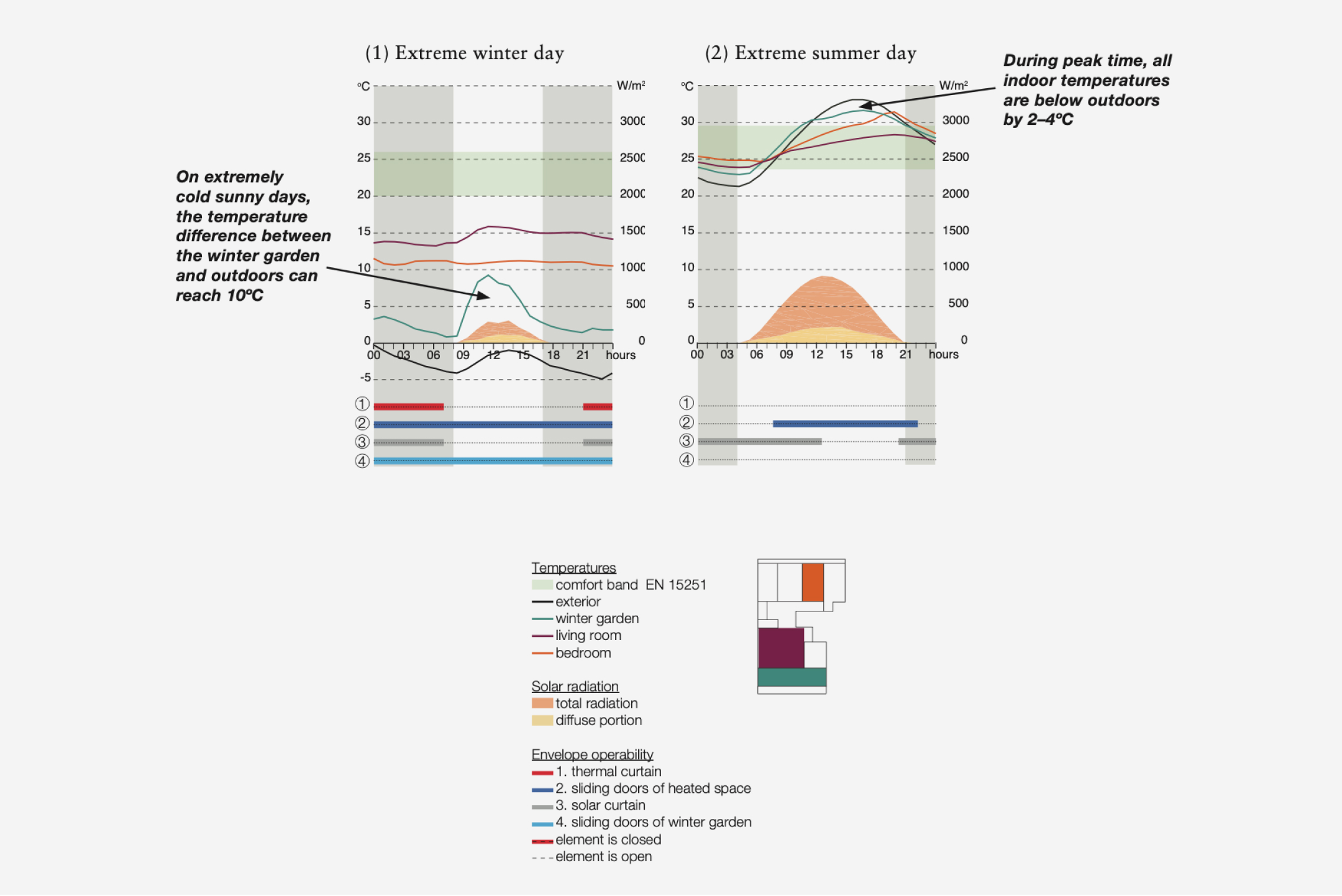

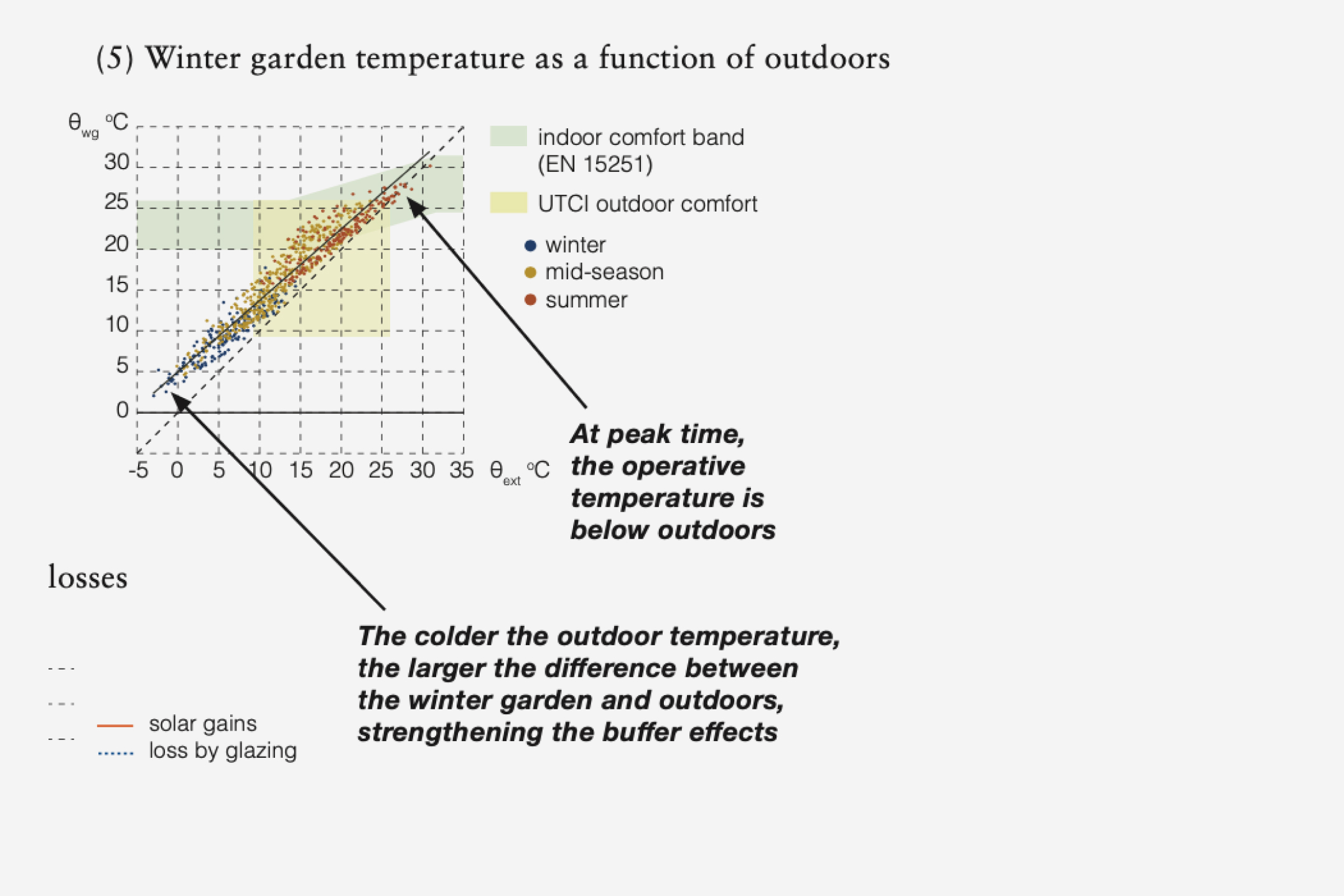

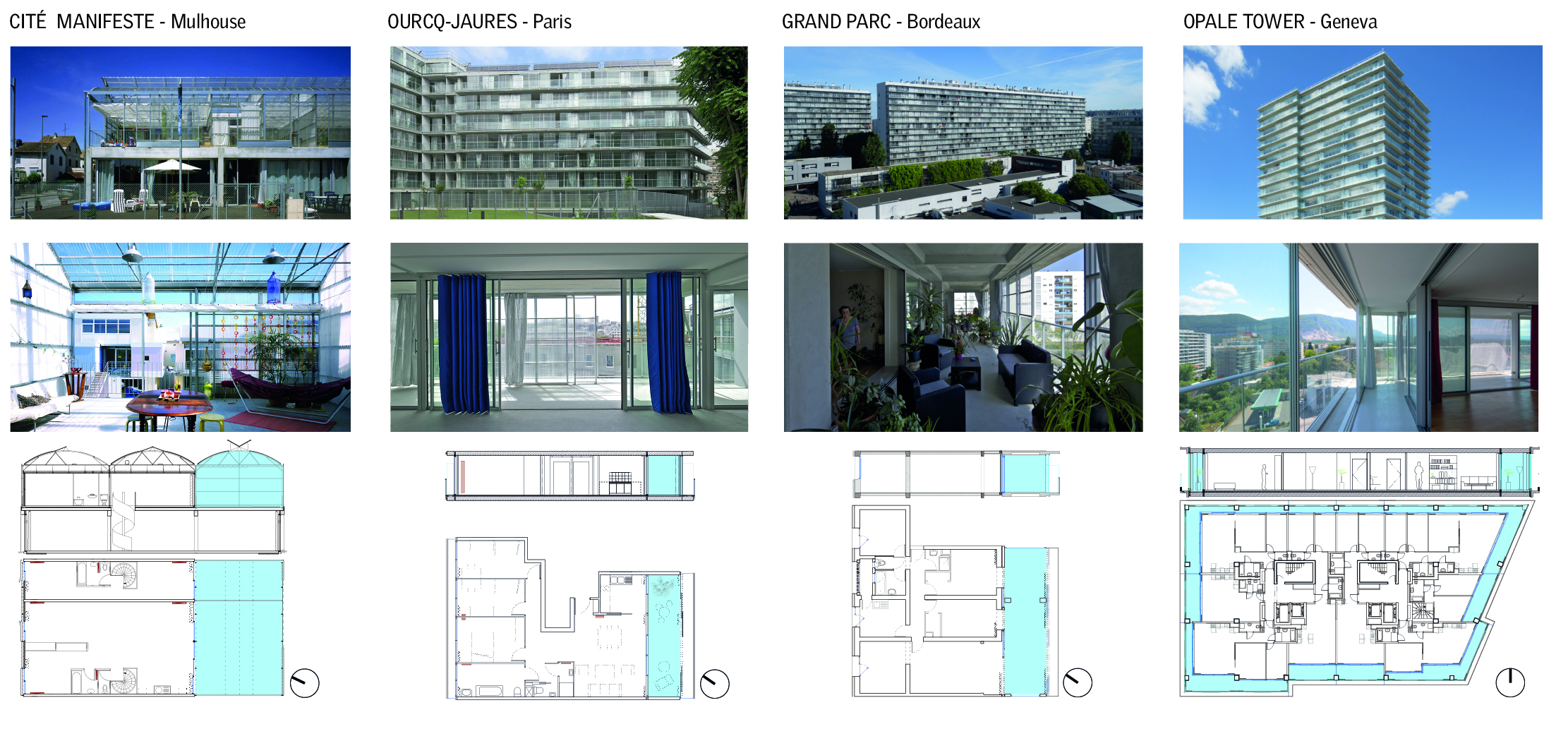

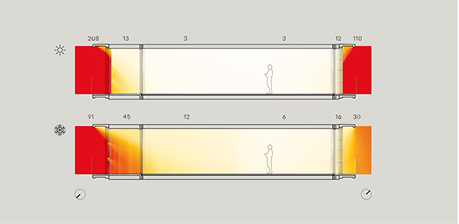

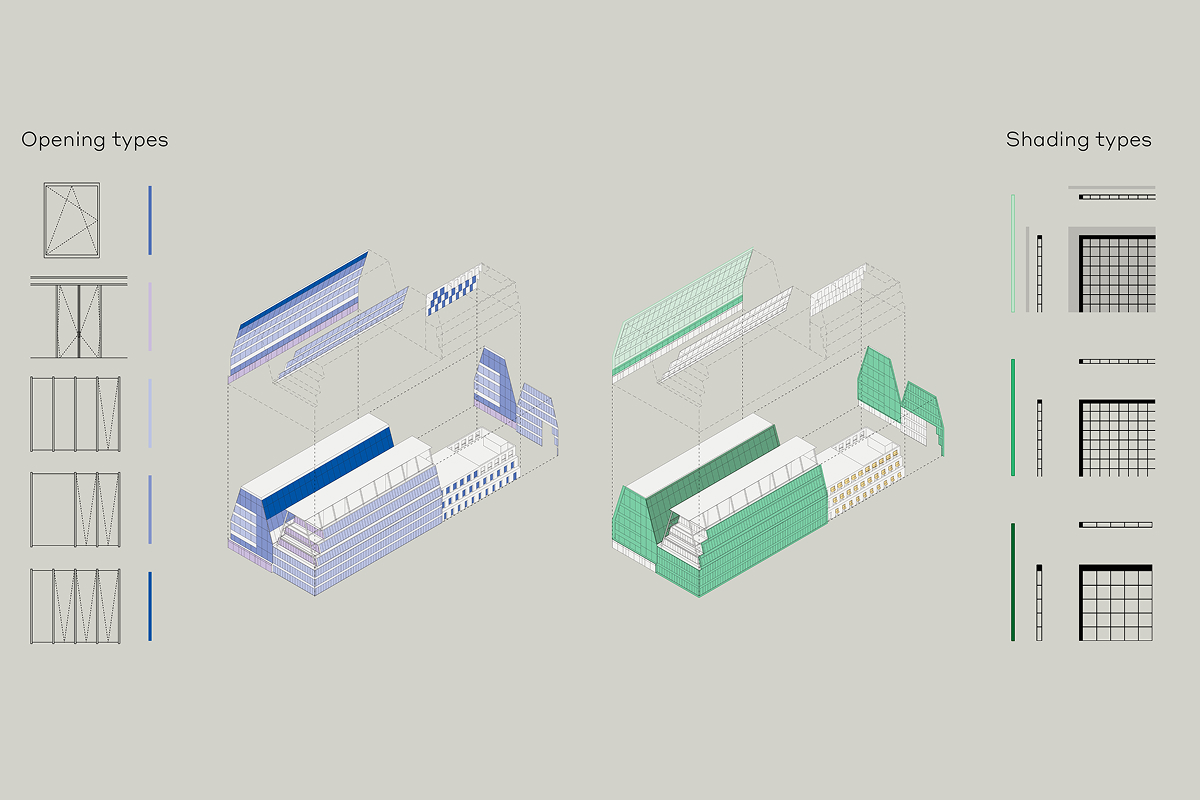

“The winter garden is a space defined by four distinct vertical elements whose position – open or closed, depending on the season, moment, or use – ensures optimal functionality. They allow users to take advantage of the climate through daily and seasonal adaptability, and allow in maximum solar gains and daylight while preserving the surrounding views and contact with nature and the environment.

In winter, both transparent facades are closed and winter gardens function as buffer spaces.

During the daytime, low solar angles enter the envelope through both glass facades. The greenhouse effect heats the winter garden, creating a natural insulation so the temperature is warmer than outdoors. At night, the heat stored in the structure during the daytime due to solar radiation is released into the space. During the summer, both facades are open, and the winter garden system transforms into a well-ventilated and weatherproof terrace that shades the interior from the high sun. At night, all layers are opened for natural ventilation. During the mid-season, the operability of the elements depends on the weather, month, and time of day. During sunny days, gentle temperatures inside the winter garden allow the occupants to leave the sliding doors of the heated space open and use the area as an extension of the indoors. During colder nights, the thermal curtain can be closed to help to maintain the indoor temperature.”

“The results of the case studies show that winter gardens not only provide more light and space but also offer greater energy efficiency and reduced reliance on mechanical equipment compared to standard procedures. More sustainable and less carbon intensive, they will be particularly resilient and beneficial for mitigating the extreme temperature challenges of the future, and what is more, a much more pleasant living experience for their inhabitants.”

Current Projects

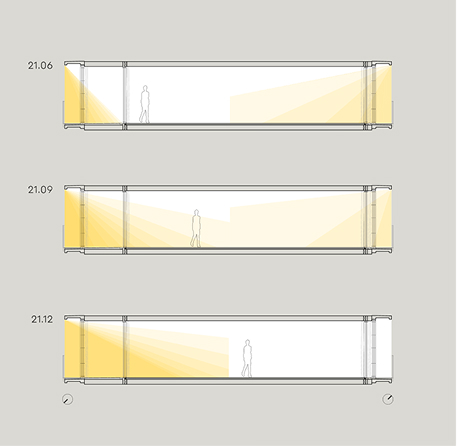

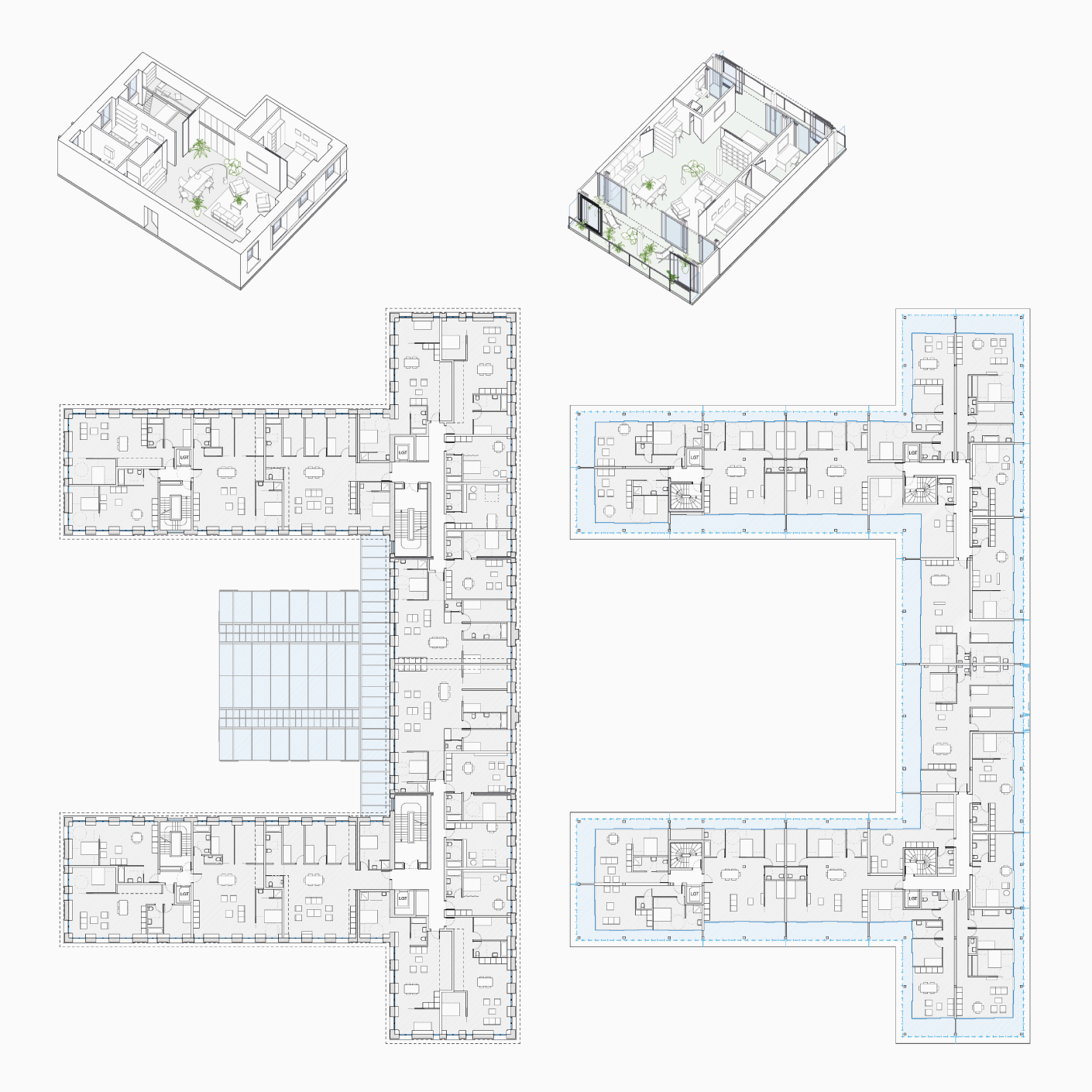

We use research to feed real practice: as a continuation of the work with Lacaton & Vassal, all the outcomes of the book were applied in the residential project of the Ilot Lelong in Saint Vincent de Paul. In Paris, the former hospital site is being transformed into a new mixed-use neighbourhood. Within that, the 1950s-era structure is slated for adaptive reuse into residential apartments. The project aims to renovate the existing, but also to densify the site and develop public space to create an urban residential district.

The architectural intentions were to provide maximum spatial quality for all housing without distinction (whether it is for social housing or standard market), and to provide generous spaces to promote appropriation. Regarding the existing, the aim was to do with its qualities, to act in its direction, to re-use it to the maximum of its capacity without destruction. This allows to build efficiently using as little material as possible.

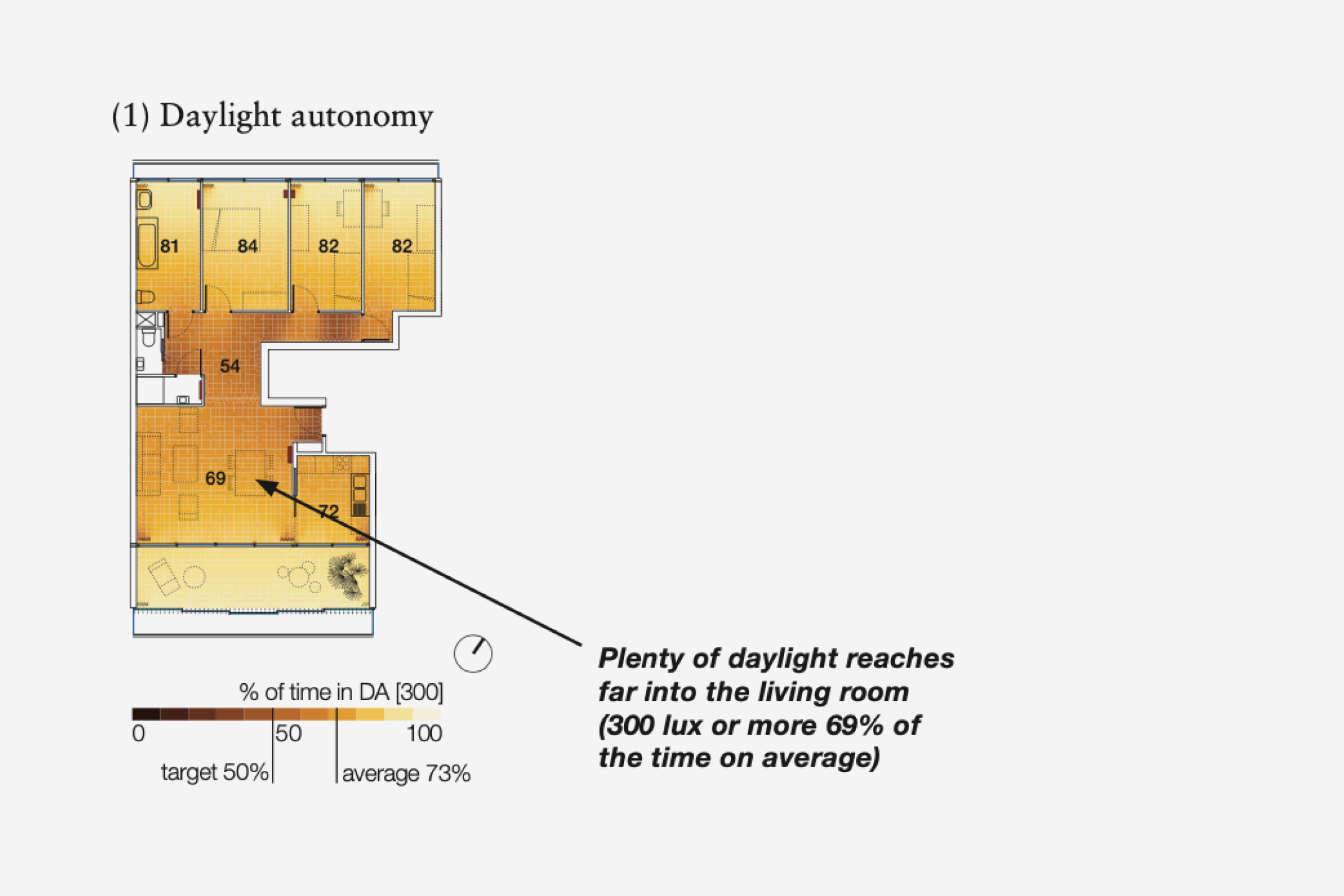

Regarding the approach, the main energy requirement of a residential building in Paris is space heating, which can be offset to a large extent by passive solar heating. The lower levels receive less sun and keep a standard window-to-floor ratio, whereas the upper levels can take full advantage of the sun with the winter garden system. In all the levels, regardless of the façade system, southern orientation was always privileged for the main living spaces, and cross ventilation is possible in most of the units. In this case, winter gardens wrap entirely the building, and its performance can be assimilated to the one of the Geneva Tower from the book.

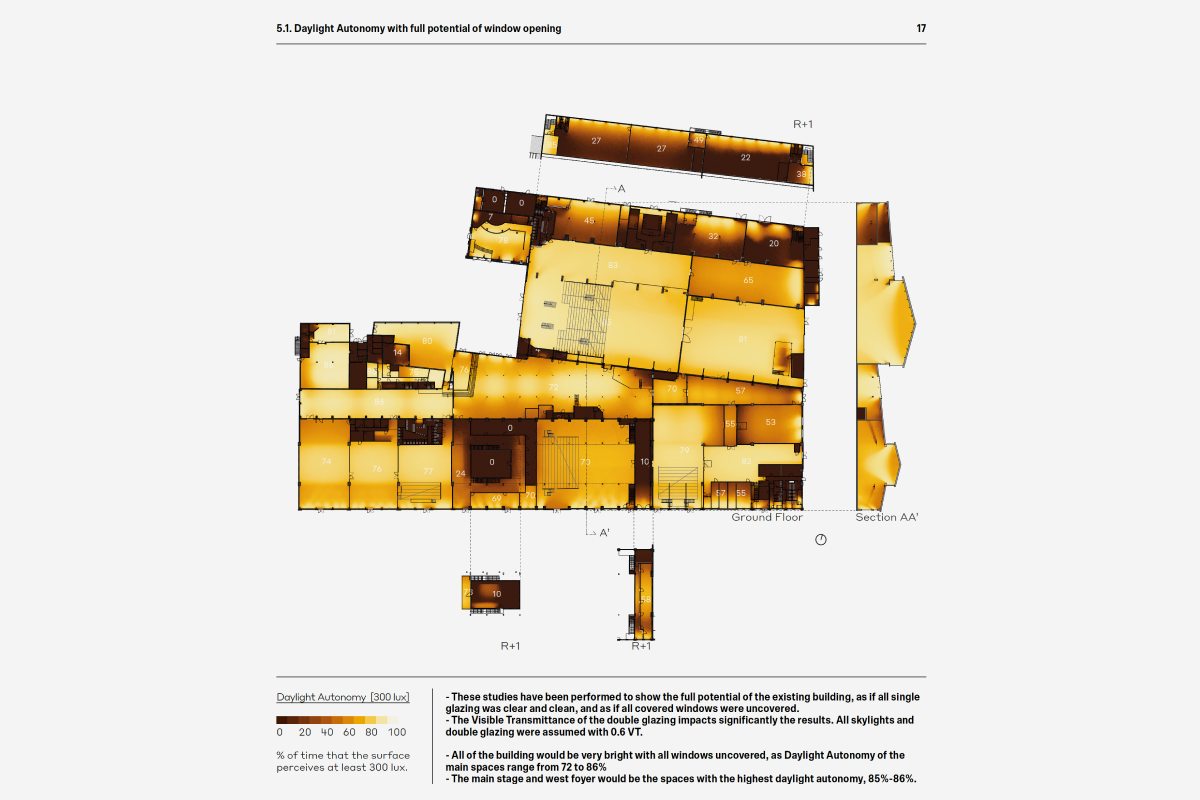

A different approach is illustrated in the renovation of the Kampnagel Theatre in Hamburg, also with Lacaton & Vassal. Kampnagel is an ensemble of industrial-era halls turned performing-arts space, hosting theatre, music, and dance. The question here was how to improve its environmental performance – especially its energy use and daylighting – while preserving the building’s raw, creative appeal. The initial intention of the theatre was to insulate all its envelope to reduce the energy demand, but this posed problems to the heritage authorities as all walls were listed. Our goal for the project was to change everything, changing nothing.

We began with a meticulous diagnostic study: surveying the current state of each space, window, and graffiti; measuring temperatures, daylight levels, air quality, and occupant behaviour; but also analysing the hourly electricity consumption, show occurrence and future projections for spectators. By calibrating a simulation model with this data, we reached an accuracy of above 87% in predicting indoor temperature, and 99% in predicting energy demand.

Regarding the necessary intervention, some of the industrial windows had been darkened or covered over time, forcing reliance on artificial lighting.

By restoring or replacing glazing, we leveraged free natural light for much of the day, which was needed when shows were not going on in the venues. Thick curtains would block light only when a show required blackout conditions. Also, we discovered that just adjusting heating schedules and setpoints – rather than running systems full-blast – could slash energy usage by 80%. The precise study of the existing enabled us to reduce energy demand to 1/5, without the need to insulate walls. Finally, the dynamic study of CO₂ concentrations according to real volumes and occupation allowed to define a ventilation strategy in each venue. In most of them, shows can last up to two hours with CO₂ remaining within acceptable levels. For longer shows, shock ventilation is needed during breaks. In the new venue, a larger capacity is allowed as natural ventilation effectively evacuates CO₂. For special shows with higher occupancy, the existing mechanical ventilation system is used, which was re-configured to feed all the spaces. In the largest venue, a new mechanical system will be implemented, only for special occasions, as the space can work passively most of the year. The building remains flexible and open, celebrating its industrial heritage while quietly performing far better ecologically.

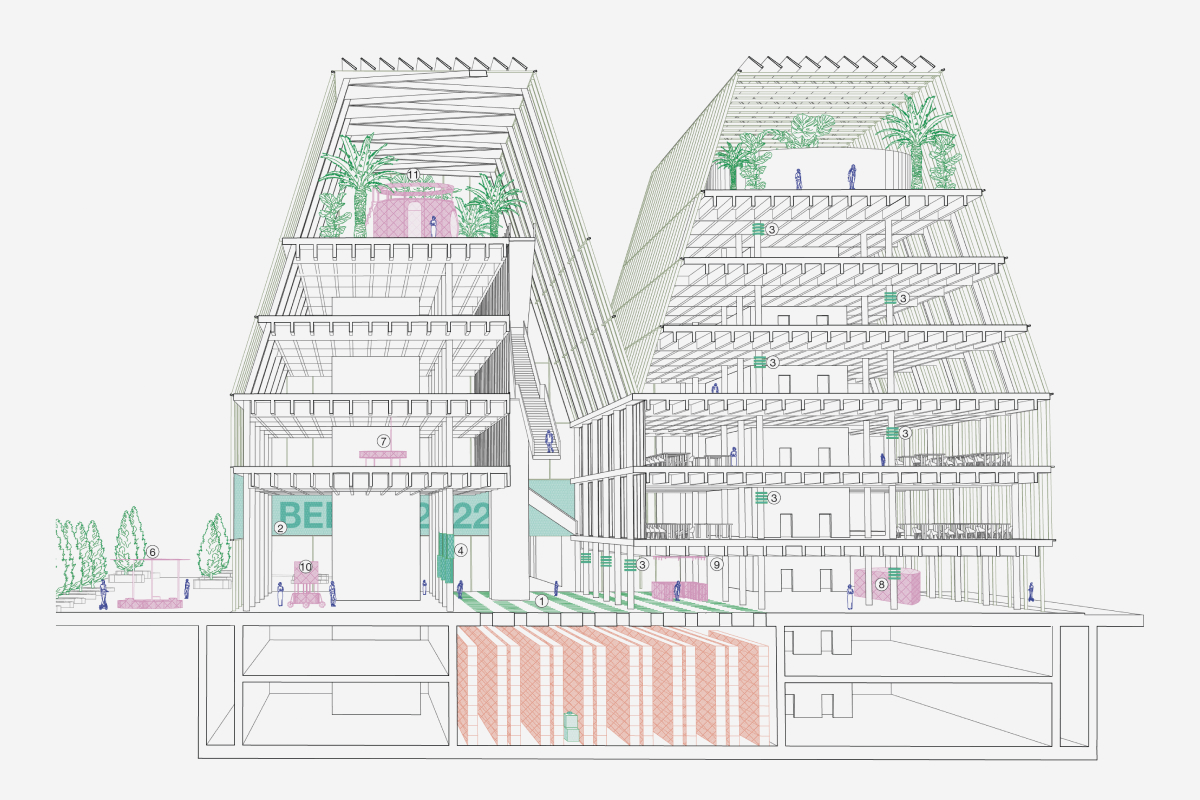

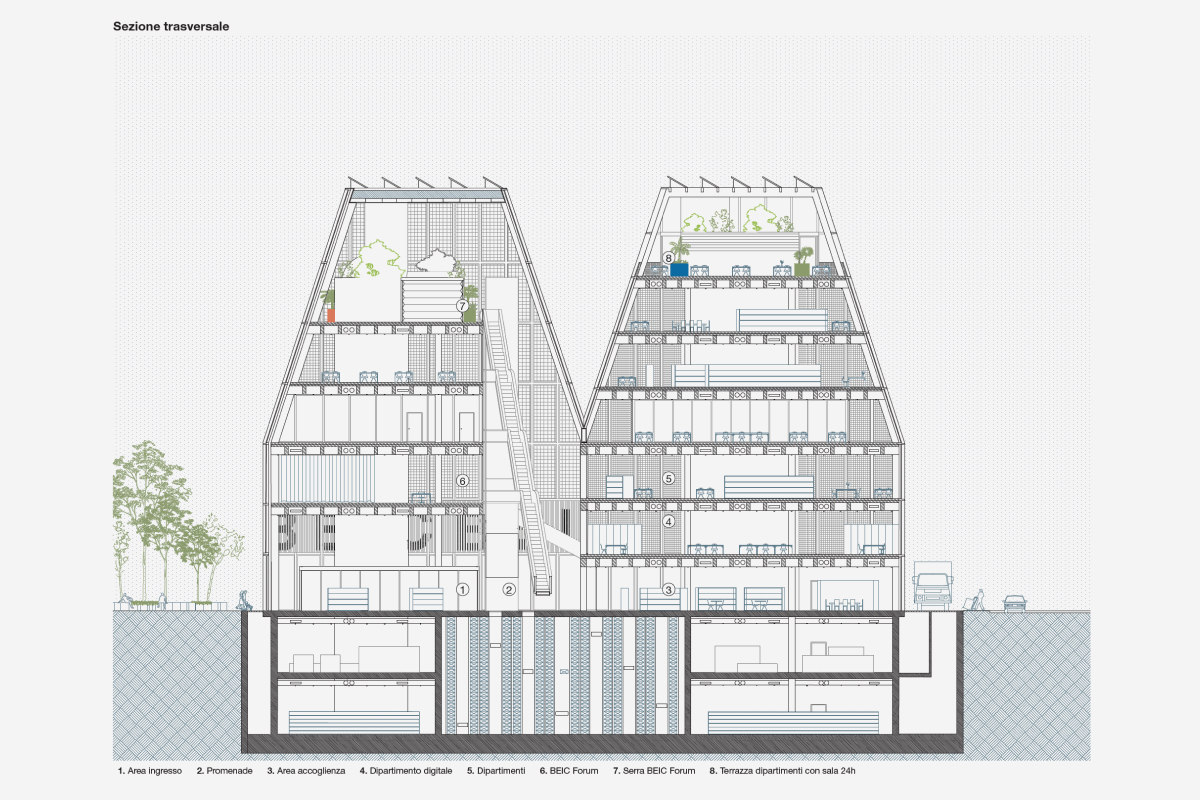

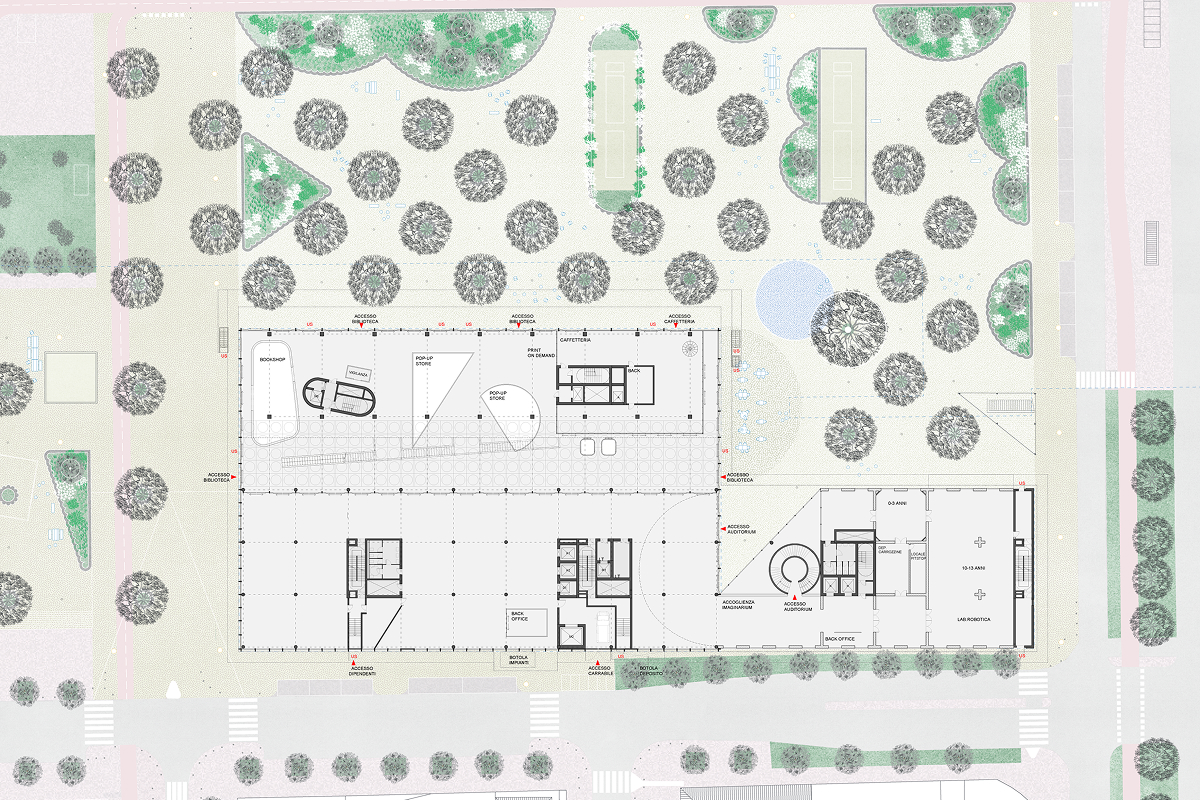

Looking at other collaborations, the Nuova BEIC (European Library of Information and Culture) in Milan was designed with Baukuh and Onsite Studio. Milan used to have very bad air quality: due to its geographical location within a valley, for being a highly dense city and in a highly industrialised area. Over decades, this air pollution started to advocate against the use of natural ventilation to provide fresh air and ventilate, which, coupled with the easiness of calculation and implementation of mechanical ventilation, completely discouraged the use of natural means. No new public building today is naturally ventilated. At the same time, building energy policies are demanding increasingly well-insulated and airtight envelopes which make buildings more susceptible to overheating, thereby escalating the need for increased cooling. However, when looking at the new air quality measurements, we discovered that the city´s long term work on its improvement is paying off, and that lower air quality occurs only in winter, when there is less need to ventilate. We therefore opted for a naturally ventilated building.

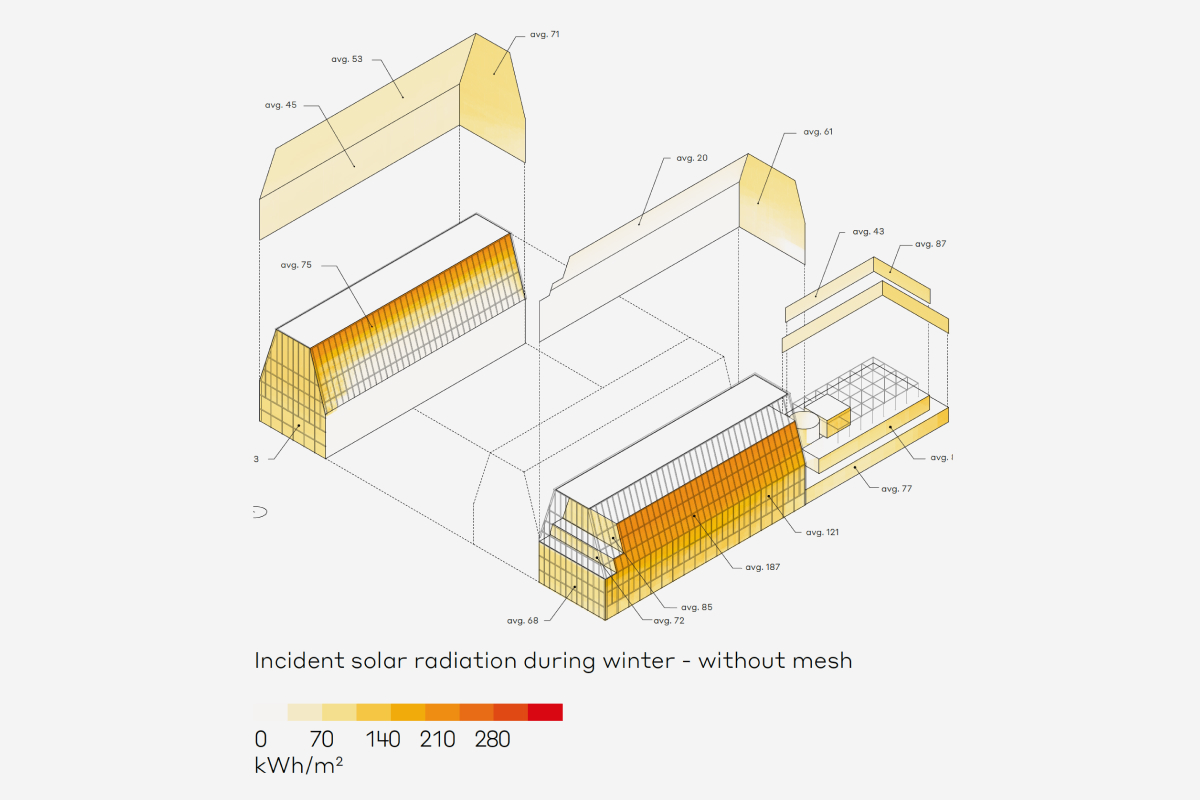

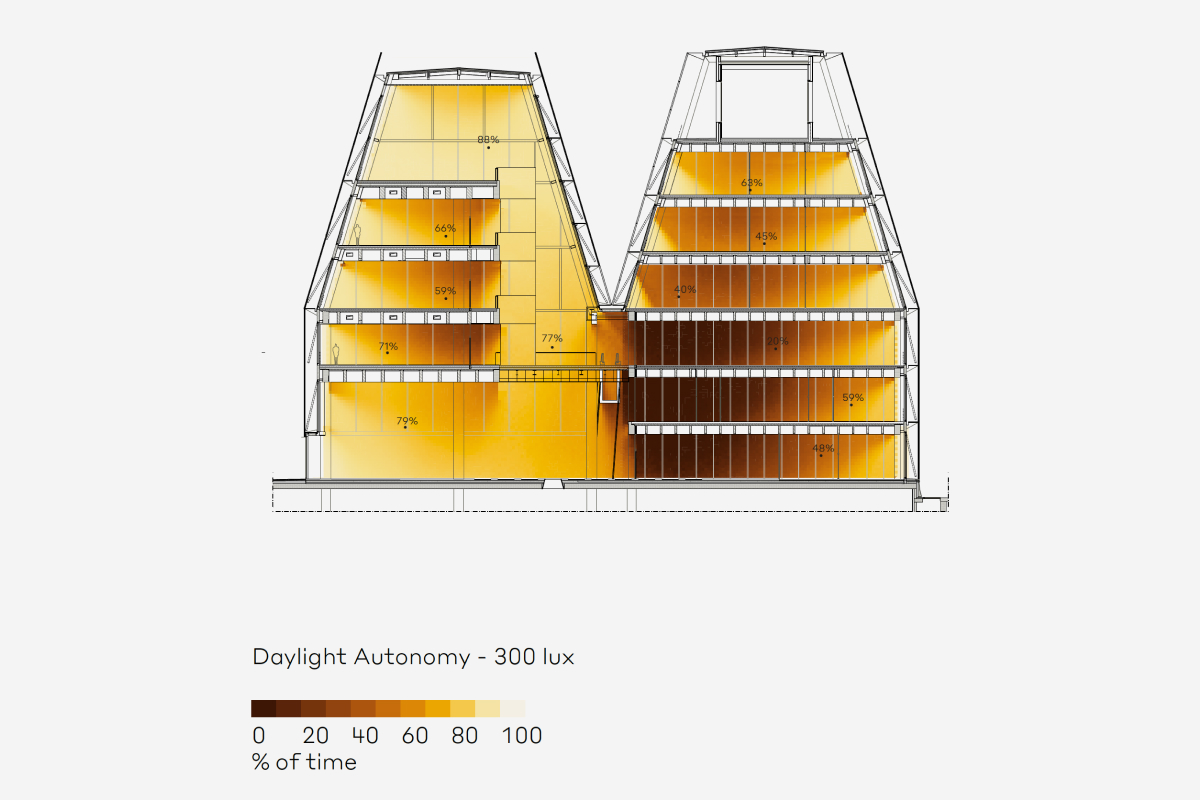

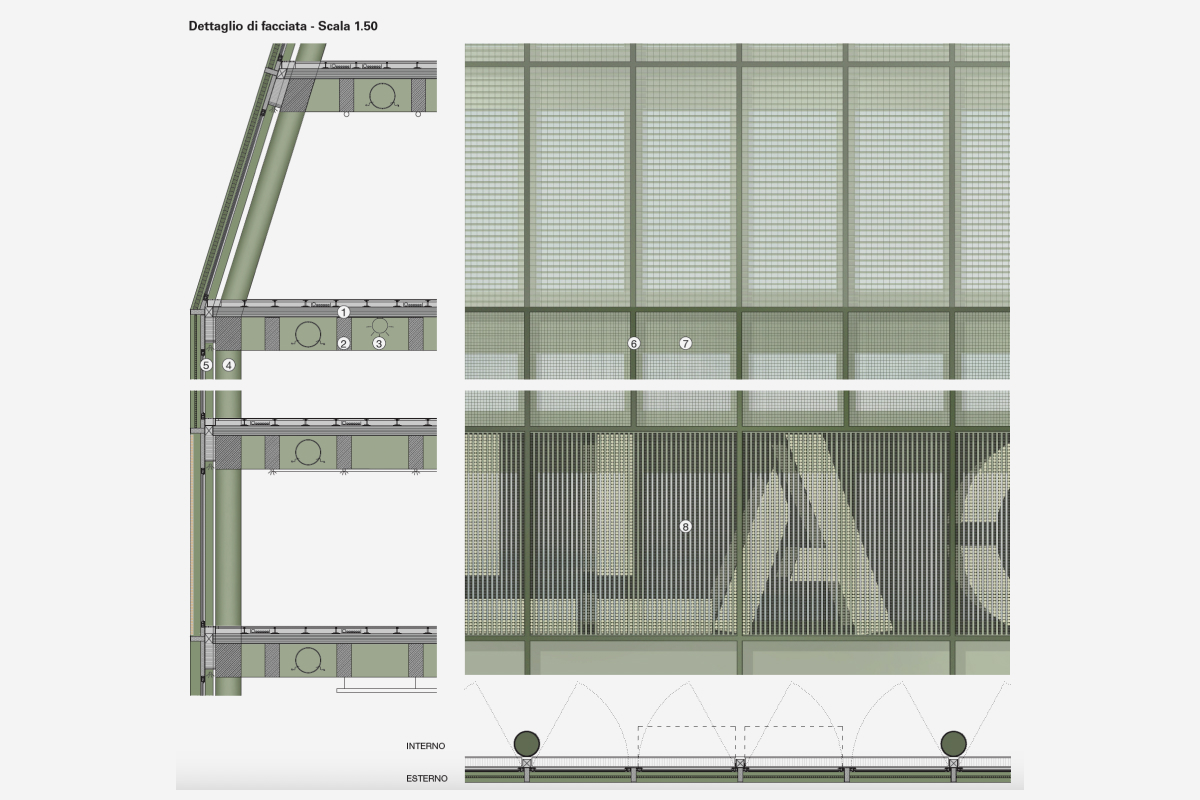

The library incorporates an unconditioned central atrium that hosts the main circulation, full of light, and acts as a transitional space between exterior and more conditioned interior areas. It is pleasantly cool in summer when its vents open, harnessing breezes, and warmed in winter by direct solar gain. Like this, only 63% of the built volume is heated. The Dipartimenti (traditional library space) with very low internal gains, is in the south nave, to benefit from the sun and heat up naturally -books remain in the core of the building, on the northern areas, whereas the reading areas are close to the windows. The Media library with high internal gains is located in the north nave to avoid coupling its heat with the sun and avoid glare. Book storage is located underground, where hygrothermal conditions are very stable across the year, tending to Milan´s yearly average (13.5ºC), which naturally prevents book degradation. The envelope is protected from the strong sun with a metal mesh, which was optimised by orientation. In all the spaces, windows are operable to ventilate when outdoor temperatures are mild, and at night. The concrete of the structure is exposed to stabilise temperatures and especially keep them cool during summer. Our analyses suggested that these strategies cut heating demand by well over half and cooling demand by as much as three-quarters relative to a typical sealed library of the same size. Beyond lowering energy bills, this approach enriches visitor experience by remaining aware of external light and airflow, connecting them to seasonal rhythms even inside.

Environmental architecture

Environmental architecture can no longer be a niche concern. Reducing energy demand and adapting to energy shortages and hotter summers calls for resilience. We see that resilience is best achieved through simplicity and natural means instead of uniform conditions. With rigour and precision, we can reach ambitious targets without resorting to one-size-fits-all machinery. In an era of intensifying climate challenges, design that embraces the seasons and occupant agency feels both necessary and deeply human. We recognise that sometimes design cannot eliminate the need for all mechanical systems, but we aim to render those systems supplementary rather than central, as adaptability matters more than chasing an elusive “perfect” environment. Listening to the climate, maximising passive means, and fostering occupant participation become fundamental for design sufficiency. These strategies, refined by rigorous measurements and simulations, reduce energy consumption while preserving a sense of connection to the outdoors, to the climate, and restoring delight to architecture. We see a clear path forward, rooted in architectural intelligence, environmental science, and an acceptance of natural variation. We believe that architecture can once again become a space of active pleasure, not mere consumption. Don’t fight climate, use it.

ABOUT

Florencia Collo. Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Florencia graduated in architecture at the University of Buenos Aires (FADU, UBA), and did post-graduate studies in the MSc Sustainable Environmental Design at the AA. She has taught History of Architecture, Urban Planning (FADU, UBA), and today she leads a course about Environmental Design in Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. She is a co-founder of Atmos Lab and also a member of the PLEA organisation (Passive Low Energy Architecture).