Beacon of Revival:

Naoshima Hall in Honmura

Category

Best practice

Author

Alex Hummel Lee

Photography

Jérémie Souteyrat

Date

29 Apr 2021

Source

Daylight & Achitecture #28 2017

Share

Copy

With his new community centre and sports hall, architect Hiroshi Sambuichi has created a central space of gathering and representation for the island dwellers on Naoshima in southern Japan. Part of an overall strategy to revitalise the island, the new buildings are intended to foster social and cultural life in the local community. Their large roofs make optimal use of “the moving materials of nature”, as Sambuichi calls them, in order to provide daylight and fresh air to the building users. The design of the buildings has been based on a combination of experimentation and advanced engineering, as well as a careful reading of the local climate conditions and existing urban patterns.

About 400 years ago on the island of Naoshima in the vicinity of a shrine, a plan for a town was laid out. Called Honmura, literally the origin village, it was conveniently positioned by the calm waters of the strait between Naoshima and adjacent Mukaejima, and it prospered for centuries on fishery and salt production. But with the sudden opening of Japan to the West and its technologies, spurring on the belated but all the more hurried coming of the Industrial Age in the country, the island soon experienced the fate of many others in the Inland Sea. Uninhibited exploitation of their resources for fluctuating economical gains laid waste to the eternal natural beauties of the islands, leaving unerasable scars deep in their landscapes. Subsequently the concentration of power and transition of production to the urban centres meant the gradual depopulation of the Inland Sea. For decades, the cultures of the once-central islands slowly decayed as the remaining aging population dwindled. In an attempt to alleviate this, the local prolific philanthropist and patron Soichiro Fukutake bought large parts of the island to transform it into a new sort of idealistic art reservation, fusing the beauty of the setting and the charm of the islanders and their culture with the dreams of international contemporary art. Some of the traditional abandoned houses in Honmura were gently transformed into entire artworks in themselves, and on the southern side of the island he commissioned Tadao Ando to build museums and accommodation for the growing number of visitors.

The project has since expanded to other nearby islands, with permanent galleries designed by famous Japanese architects, including Hiroshi Sambuichi’s Seirensho Art Museum and Kazuyo Sejima’s Art House Project on Inujima, as well as Ryue Nishizawa’s Teshima Art Museum. In addition to this, Fukutake hosts an art triennial in the area, last time involving 12 islands and attracting a yearly attendance of no less than 1 million visitors, an astonishing feat for such a remote place with difficult access.

“The huge roof of the gymnasium is externally clad with hinoki wood, which has turned silvery grey under the influence of the weather since the building was opened.”

Street crossing under a large roof

Despite the overwhelming success, Fukutake has recently endeavoured to influence societal change in the area much more directly. As an example of this, he asked Hiroshi Sambuichi to give proposals for a strategy for the future development of Naoshima, prompting the architect to embark on an ongoing research project that, after 2½ years, materialised for the first time in the Naoshima Hall. Commissioned by the Naoshima municipality, the small complex consists of a community centre and a gymnasium for the inhabitants and visitors of Naoshima.

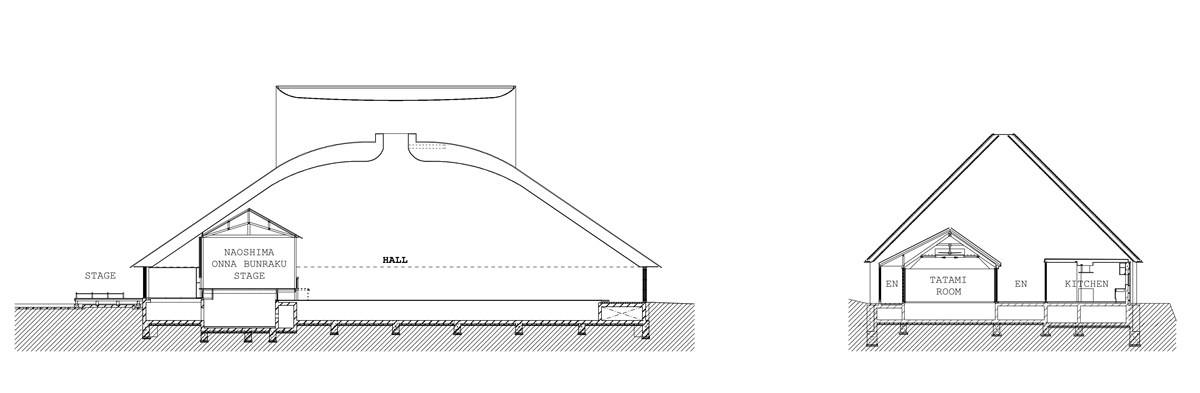

The streets of Honmura flow through the interior of the community centre, consisting of four separate rooms under one large roof, the apex of which provides daylight through an opening. Two layers of louvres integrated into the opening let rain trickle to the ground while filtering the wind. In addition to a large communal kitchen and a public restroom, the two main rooms are meeting spaces floored with tatami mats, for the occupants to convene during festivities and events.

It is, however, the iconic gymnasium that attracts most attention, with its grand roof clad in hinoki wood. In form, it resembles the traditional irimoya hip-and-gable roof, but with a great void under its ridge and eaves so low to appear as if the building grew from the mounded moss landscape surrounding it. But when passing through its latticed entrance, the impressive spacious interior is revealed instantly. Here, the hall appears nestled between heaven and earth − the encompassing narrow band of windows at eye height giving a restricted view to the slender stems of the trees surrounding the hall and the vast, softly luminous white surface of the ceiling as an overcast sky. Onto this, the ambient light, which illuminates the hall in the day, faintly reflects the vivid colours of the sky outside and the almost fluorescent moss of the landscape.

“Thinking about the earth’s details is integral to my thinking about architecture. Reading in minute detail the site’s topography, climate and other environmental factors is among my most pleasurable activities as an architect.”

The light was considered with meticulous care. When serving as a gymnasium, the hall hosts badminton, in particular. Though illuminated by daylight, it was important to block the glare of direct sunlight that would blind the players. To keep the space sufficiently lit, traditional Japanese shikkui plaster (reportedly the largest continuous surface of this material ever made) was chosen to reflect and distribute the ambient light softly and evenly. In the centre of the ceiling is an opening through which diffuse light gently pours down from the remarkable triangular void inside the ridge of the roof. The purpose of this feature is however not the distribution of light but air.

For as is customary in Sambuichi’s architecture, the greatest effort in the Naoshima Hall was made by ensuring a pleasant natural ventilation. As the building has two very different and demanding requirements, this was a very delicate task. Apart from being a gymnasium for badminton, the hall also hosts performances of puppet theatre and, as a venue housing up to 300 seated spectators, requires a significant exchange of air. And while badminton also requires a constant supply of fresh air, it must never move so quickly that it will interfere with the sensitive motions of the main object of attention – the aerodynamic shuttlecock.

Eventually, it turns out that the only permissible motion of air is gently upwards. To initiate this, an updraft is created inside the building by the winds of the site. Just as the light of the sun is let in only by reflections and never directly, so the air in Naoshima Hall is set in motion indirectly by the wind, which never finds ingress by itself. Instead, it flows through the large void in the roof ridge, the shape of which acts as a funnel, compressing the air to lend it velocity while lowering its pressure, a phenomenon described by the Bernoulli principle. As it does so, it creates a veritable microclimatic low-pressure cell inside the void, which steadily pulls out the air from the interior space of the hall below. This air is then continuously replaced by a flow running from inlets in the surrounding landscape, led underground through a complex of ducts to cool it down by the thermal energy of the earth, and released through vents in the floor. Thus, the only phenomenon pulling at the air at any time is the indirect effect of the local wind.

“I think each work of architecture must possess a form and appearance the earth will accept.”

Harnessing the moving materials of nature

We will get back to this mechanism, but first we must take a look at Sambuichi’s unique approach to architecture. For though it may have related passionate contemporary proponents in various types of sustainability and site specificity, Sambuichi does not read books or follow ideologies. Instead, he claims to take his philosophical advice from but one source − his relation to planet Earth. He calls his architecture “details of Earth”. This implies that he does not harbour an ideal of saving the planet, rather that he has a profound interest in playing with the workings of earthly phenomena. It is a personal sense of obligation to Earth, not in the sense of spiritual submission but rather with the simple recognition that Earth only nurtures that which suits it. And though this approach is not directed at society, it may, in turn, indirectly become the most earnest obligation to it.

For architects concerned with sustainability today, digital tools and data abound, enabling precise models, statistics and simulations of the conditions of a site; the architect may not even need to leave the comfort of the office to investigate a site. But Sambuichi insists on visiting and investigating his sites innumerable times, with his often self-built measuring instruments and uses himself as an atmospheric sensor. To him, reading the Earth means to read material motions. Often voicing his neologism of “moving materials”, he considers the fluid materials of the environment, such as air and water, before the traditional architectural building materials, as progenitors of architectural form. Sambuichi talks intently of the cycle of Earth and refuses to acknowledge a division between human and nature or man-made and natural. All entities are equally effected by and affecting the moving materials. That is why he insists on describing his architecture as ‘details of Earth’, not as buildings mimicking nature but as architecture that makes use of the mechanisms of material motion. For an architect to mediate movements of materials in a construction of an architectural phenomenon, a virtual presence by digital data does not suffice; rather it requires that he reads the moving materials with his own body.

That is not to say that he abhors computers. For most projects, he enjoys a close collaboration with Arup Japan, which also provided extensive simulation and advice for the projects on Naoshima. Computers have their strength in the original purpose embedded in their etymology, as machines to compute data, a repetitive task that could be tedious and error prone if done by architects. They are not guided by architectural intuition and only make use of the parameters given. Meanwhile, Sambuichi continues to perform his own experiments in the office, where a wind tunnel has been made with careful precision, although constructed of cardboard, with smoke coming from incense and the fan being of the home appliance type. With this setup, the air flow of buildings is tested to be further refined by the computer simulations done by Arup.

“People love and respect the places where they live; they appreciate these places’ beauty and richness. Architecture accepted both by the earth and by the people – this is the kind of architecture I am striving to create.”

Reading the site and its hidden messages

This period of experimentation seems to be Sambuichi’s prime time and, if allowed, he extends the research period, continuing his experiments even after the building is made. For these idiosyncrasies, his approach is often met with astonishment from outsiders. And yet, it is evident to all that his method is not mystical or obscure and the appreciation of its fruit does not require the construction of an abstract elaboration – it is evident to those keen to natural sciences, appearing more as a recollection of what buildings are originally about.

This isn’t odd, Sambuichi explains. Moving materials are the base of existence. Humans may live without possessions but cannot survive without air and water. And luckily, they are reliable. We may be sure that the sun will rise again tomorrow morning, and that it will make the winds blow and clouds rain as always. Our technologies may not be as reliable. Basing an architecture on the most basic energies is Sambuichi’s endeavour. But energies, in every place, are different in velocities and directions due to countless factors of their situation; and in adapting to moving materials, Sambuichi’s architecture becomes integrally site specific, one may even say endemic, similar to how buildings of the past relied on local material movements. As such, he sees the moving materials as the origin of cultures, that the livelihood and customs of people rely on the available local energies; the houses and towns of people to be read as diagrams of forces. This was also evident in Honmura, on which the Naoshima Hall in all its details is based. After years of research conducted by Sambuichi’s office, a pattern appeared, a carefully planned urban layout revealing a prevailing wind direction and a way to make use of it.

All houses are oriented similarly, placed with small gardens south and north to create a passage of wind. They are laid out in a grid resembling a folding fan, the southern pivot of which is the source of the wind. This blows gently from a valley, over rice terraces that cool it in the summer. Since the founding of the town, the people of Honmura have shared this wind, relaying it from house to house by the layout of the houses. It is the same wind to which the roof of Naoshima Hall is oriented.

Sambuichi saw in his discovery of this ancient building custom a letter from the distant past about the moving materials of the island and obliged to continue its tradition born of moving materials.

Thus embedded in the nature of Naoshima, the building has become a contemporary symbol for the people of the island,with which they may understand and represent themselves as they receive large numbers of guests from around the world every year. They may come to see performances of the unique Naoshima Onna Bunraku puppet theatre, which finally received in Naoshima Hall a space dedicated to its art spanning centuries.

The stage is placed so they may rehearse by using the intimate space of the back of the stage. At night, when the light of the hall seeps through the ceiling to the triangular void of the roof to light it up as a beacon, it gathers the people on the island. And perhaps they may, as is Sambuichi’s dream, contemplate how cultures have gathered across the globe and centuries, relaying cultures based on moving materials from the ancient past to the distant future.

Client: Naoshima Municipaility, JP

Architect: Hiroshi Sambuichi Architects, Hiroshima, JP

Location: 696-1 Honmura, Naoshima, JP

Alex Hummel Lee is an architect, architectural writer and currently a PhD fellow at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture. Born in Copenhagen, he has worked with architects Lundgaard & Tranberg in Copenhagen as well as Hiroshi Sambuichi in Hiroshima, where he became an associate partner in 2011. One year later, he also established his own office, atelier a.lee, in Copenhagen. Alex H. Lee has edited a number of books and special issues of magazines on Hiroshi Sambuichi. He is also a regular author of Arkitekten and Arkitektur DK and a contributor to magazines such as Japan Architect and Shinkenchiku, GA.