Designing spaces of vitality and liberation

Category

Best practice

Best use of Natural Light prize

Daylight & Architecture

Design Philosophy

Author

Jadrana Ćurković

Photography

Tomoki Hahakura

©Osamu Morishita Architect and Associates (Illustrations & Animation)

Date

October 2024

Share

Copy

The thoughtful use of natural light can transform spaces, enrich human experiences, and broaden perspectives. These principles shine through the work of Osamu Morishita Architects, whose innovative designs harmonize with their surroundings. Awarded the Best Use of Natural Light prize at the World Architecture Festival 2023 for their project See Sea Park, Osamu Morishita shares his beliefs and responsibilities as an architect. In this interview, we explore the philosophy behind his works and the valuable lessons he has learned throughout his architectural journey.

You were the winner of the Best Use of Natural Light prize at the World Architecture Festival in 2023. Could you please share with us your process for integrating natural light into the design of the Sea Park project, starting from the initial concept stage?

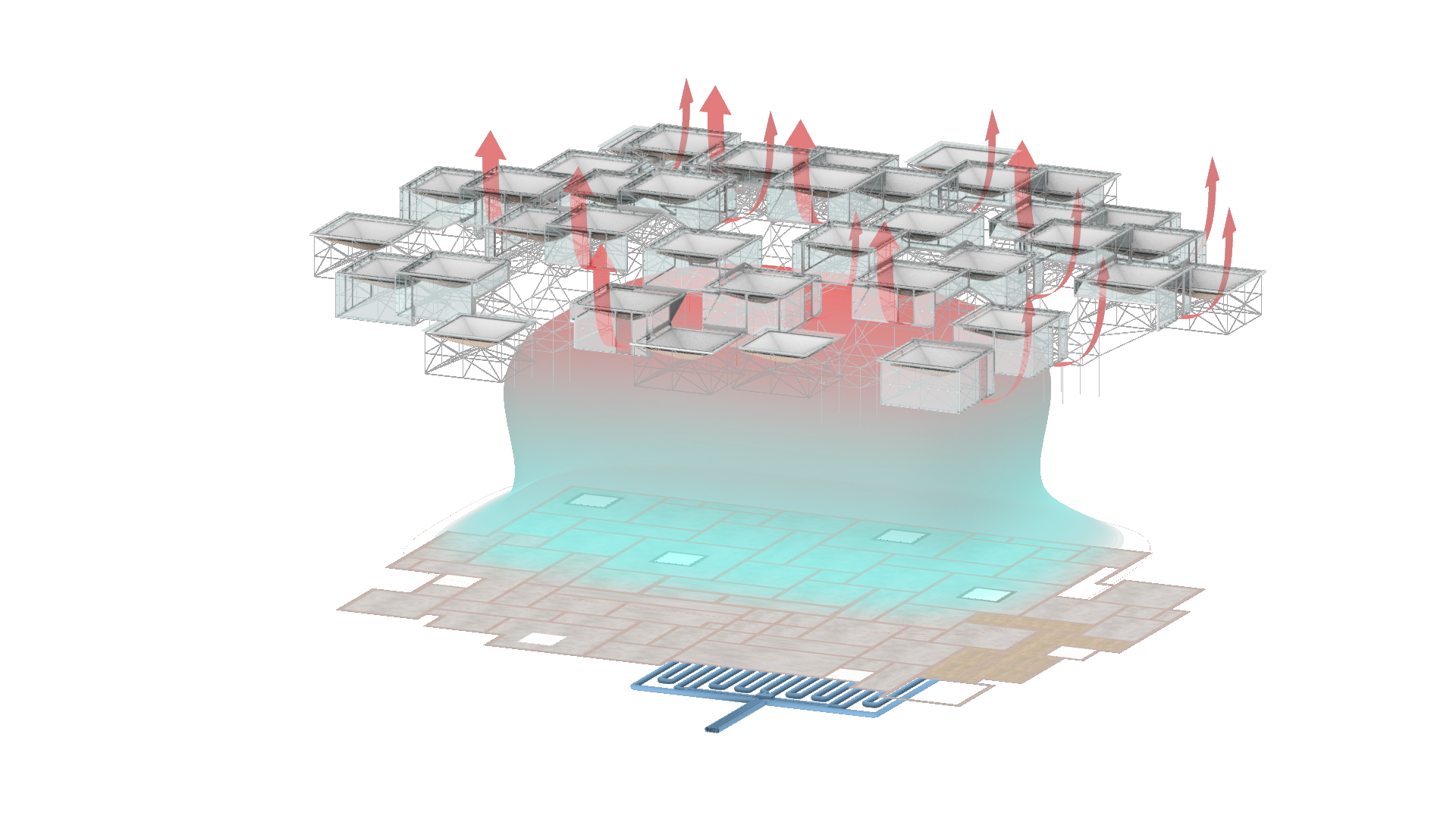

See Sea Park is designed as a space where people can experience vitality and a sense of liberation, making the role of daylight crucial in this project. Our goal is to attract and engage people with architecture, not through unique shapes that catch the eye, but by creating a variation in density through homogeneous spatial units. This approach fosters diversity within an ordered environment. We aimed to create an experience beneath the clouds, where sunlight diffuses gently through the clouds, connecting the space to the surrounding community.

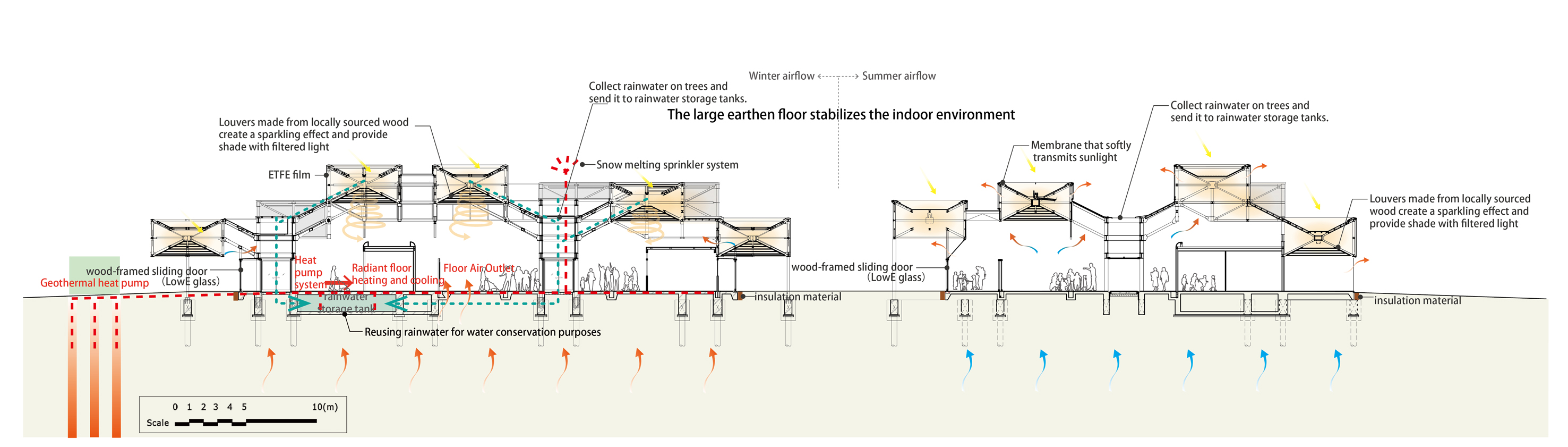

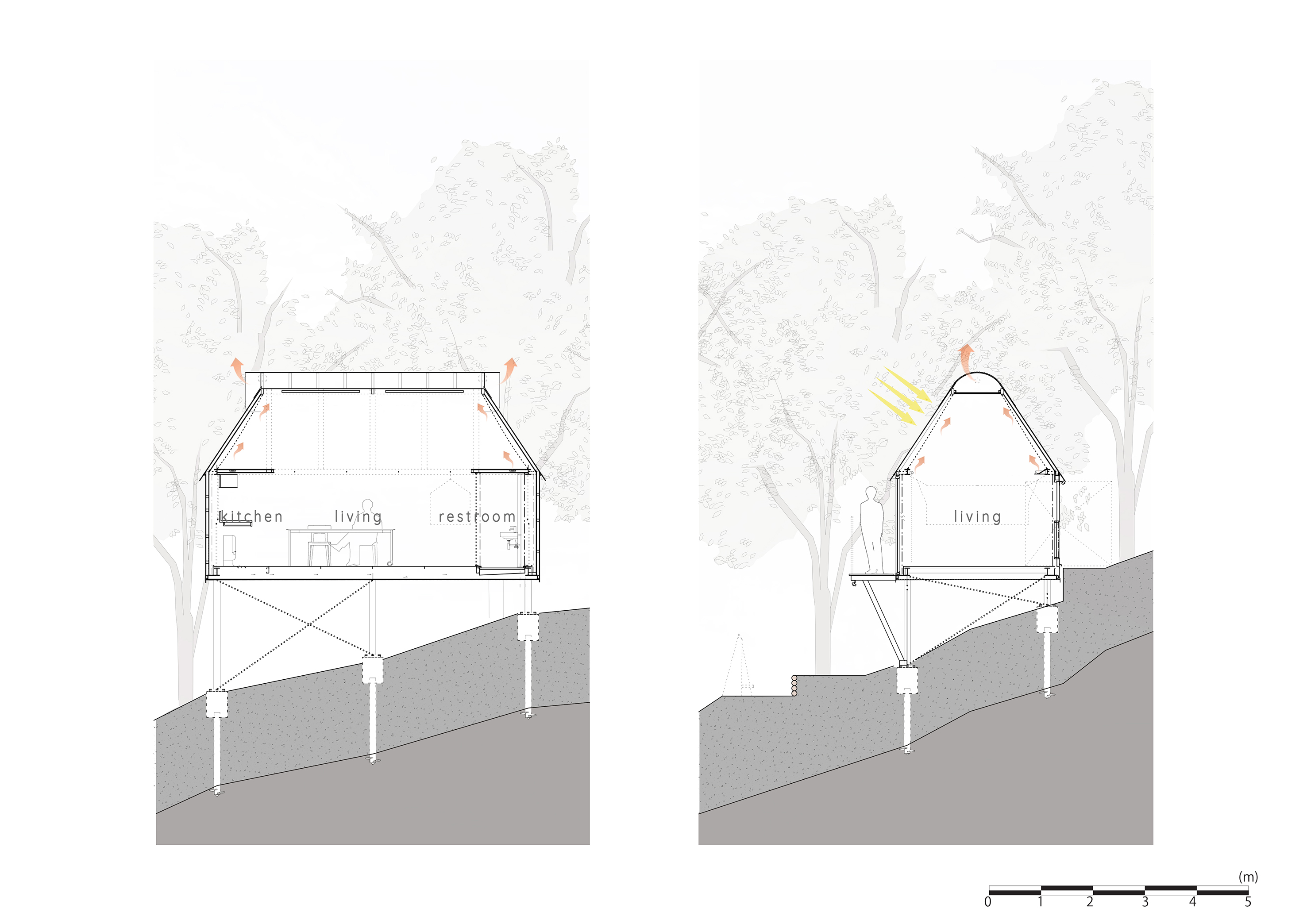

In this project, instead of using a tiled roof with high heat capacity or a thatched roof that retains air, we developed units composed of air masses covered with transparent ETFE (fluoropolymer film). This design acts like a down jacket, exchanging energy with the outside while stabilizing the internal environment.

Each unit serves as both a structure and a volume that buffers the internal and external environments. The ETFE membrane allows sunlight to penetrate, while the wooden louvers on the underside store thermal energy from direct sunlight. This setup suppresses excessive heat from entering while evenly distributing light throughout the space.

In summer, when the unit’s internal temperature exceeds the outside air, the heat is expelled through ventilation windows and the ETFE membrane. Conversely, in winter, fans facilitate airflow to return heat from solar radiation to the interior, while at night, the space above the square roof remains close to outside temperatures. This creates a gentle buffer zone, akin to the air mass in a down jacket, insulating against extreme heat or cold at floor level.

Additionally, sunlight diffuses through the structural prism of cedar louvers, filling the interior with soft, natural light. The varying heights of the units allow for different qualities of subspaces, mimicking the experience of being under clouds or mountains and enabling light to flow at various levels within the space.

Rather than adhering to traditional energy-saving methods that rely on highly insulated and airtight walls with mechanical systems, we aspire to create an open, gentle environmental control that connects to the natural atmosphere and surrounding culture.

"We aspire to create an open, gentle environmental control that connects to the natural atmosphere and surrounding culture."

Architect Louis Kahn once said, “The purpose of light is to create shadows, and shadows exist to create emotions.” This sentiment is echoed by Japanese novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, who emphasized the interplay between light and shadow in creating a pleasant space. In See Sea Park, the balance among users, architectural design elements, space, lighting, shadows, and nature is maintained throughout the day.

The design allows sunlight to enter while the square roof beneath the units—reminiscent of the ceilings in traditional Japanese folk houses—features wooden louvers that create reflective patterns on the floor. The shadows cast by furniture and plants contribute to a gentle ambiance, enhancing the interior’s atmosphere. By utilizing daylight effectively, we create moods, guide movement, and highlight key areas within the park.

"This thoughtful integration of natural light not only enhances the aesthetic experience but also promotes energy efficiency by reducing reliance on artificial lighting."

Moreover, the shadows from the structure during the day and night lend a timeless quality to the park. This dynamic interplay among people, space, design elements, and nature fosters a harmonious environment that benefits both present users and future generations.

Your studio is known for its unique approach to blending tradition with modernity. Is this the principle guide you follow in your studio? And how do you find the balance in your projects?

Perception is key to understanding architecture—it’s about experiencing the space for yourself. When I asked children and architecture students to draw their homes, they typically sketched simple shapes: a house with two sloped lines for a roof and a rectangular or square base. These shapes are immediately recognizable to the eye. However, for architects it is essential to understand the reasons behind these forms. For example, the angle of the roof slope is often influenced by the climate of a particular region.

Through our experiences and communication, we’ve developed a shared concept of what a ‘house’ looks like. I incorporate this idea into my work to evoke something familiar in people’s minds, based on their earlier perceptions. This approach makes architecture feel more engaging and relatable to them.

Perception, support, function, and systems are crucial in architecture. Thinking about structural elements is like understanding metabolic processes—just as our bodies complete daily metabolic functions, our creations should align with this concept of continual adaptation. In my work, I explore new architectural compositions, but they are always rooted in the traditional ideas I mentioned earlier.

Could you highlight a project or moment that you believe was a turning point for your studio?

There are three significant projects for key clients that we are currently designing and that are still under construction. One of them is the JST Product Complex project in Okayama, which presents innovative and sustainable challenges. Completed projects like See Sea Park and Think Stay Mt. have also been crucial for my studio. As an architect, I find the most challenging aspect is communicating our design philosophy to clients and society to gain acceptance for our approach. It’s essential that our work not only influences society positively but also aligns with sustainable ideas.

Please tell us the story behind Think Stay cabins. Did you create this space as an alternative work location? The cabins are immersed in nature, and the design highlights essential architectural features. Is this a definition of a creative space for you?

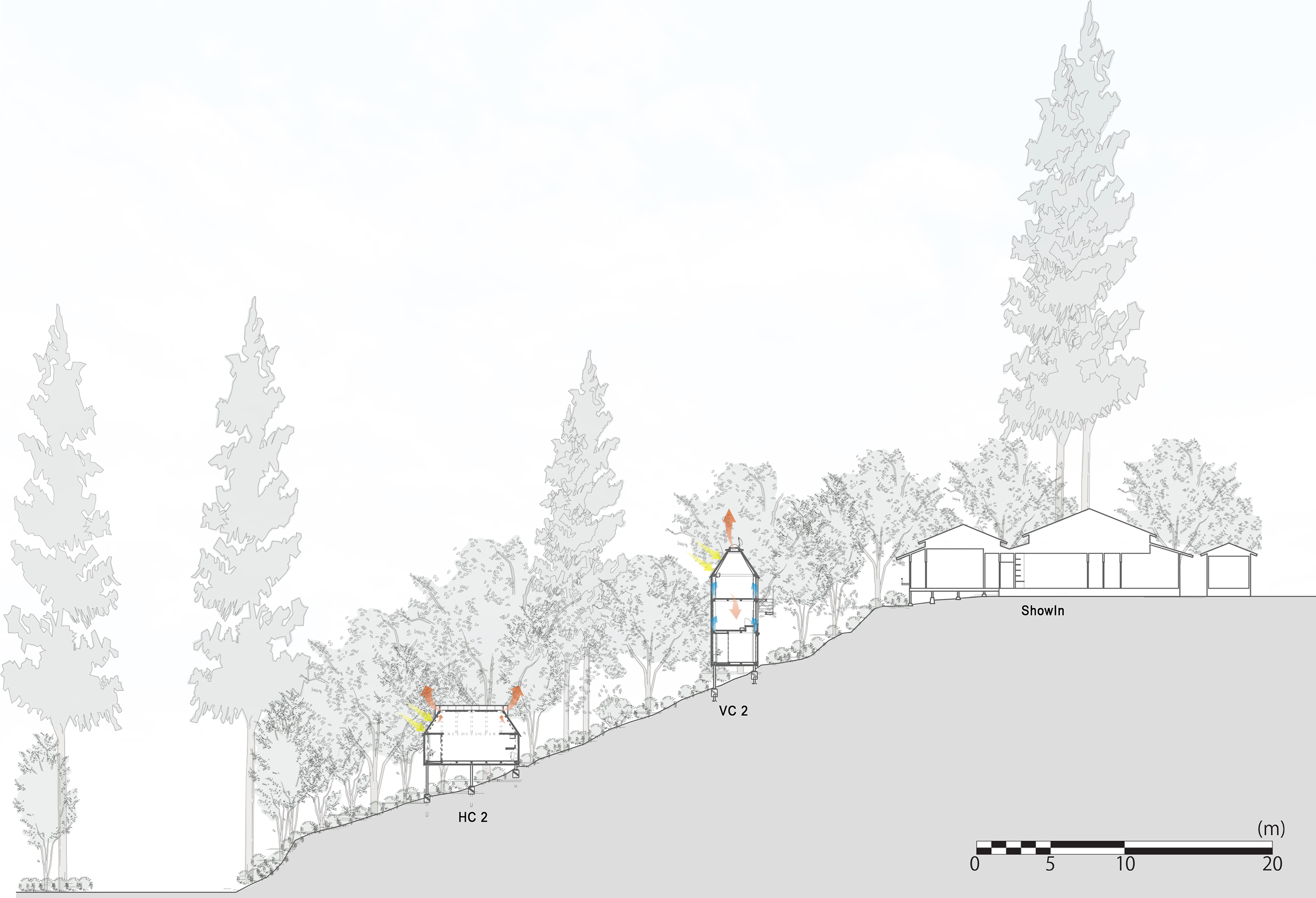

The initial plan was to renovate the decaying Sukiya House as a villa or satellite atelier. However, the dense vegetation on the 5,300 square meter site made it challenging to navigate, with no paths or infrastructure. To maintain the area, we needed to generate revenue, so we decided to create a rental atelier, a space for creativity and community engagement. I worry that Japan’s creative spirit is waning, and I hope this land can help revive it.

When we first saw the overwhelming vegetation, we thought it would be impossible to proceed. However, the COVID-19 pandemic shifted our perspective. Feeling isolated and yearning for a new living space, I proposed to the landowner that we could develop this area as a “third place” for society, not just a secluded retreat.

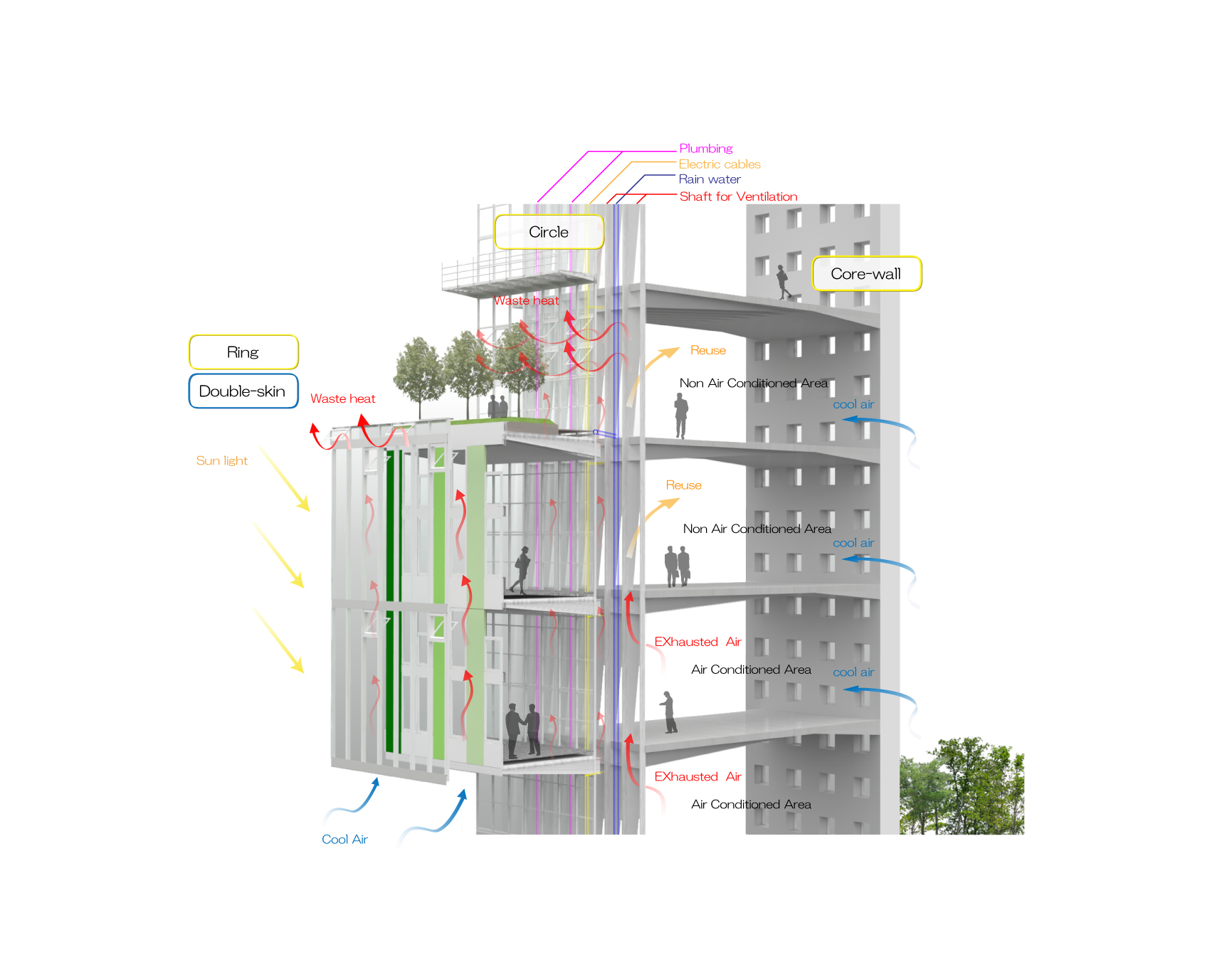

My vision aligns with a concept I proposed during my graduation design—a complex climbing the Rokko valley, creating spaces that feel elevated and connected to nature. I aim to experiment with ways to control the thermal environment while minimizing reliance on mechanical systems.

Ultimately, the pandemic reignited my desire for a better society, inspiring me to create a space where people can gather, reflect, and enhance their sensibilities. I envision Think Stay as a place to escape daily routines, fostering meaningful connections in a serene natural setting.

"Our goal is to embrace natural seasonal variations, promoting a balance between comfort and environmental harmony while reducing life cycle energy consumption."

The project has been completed a year ago. How is it spending time there now?

Rather than offering luxury services, the concept of this space focuses on allowing individuals to enjoy their time and care for themselves in an environment conducive to creativity and reflection. Over the past year, people have begun to appreciate this philosophy more deeply, which brings me great joy.

The atmosphere, temperature, and interaction between people and the architectural space are now well-balanced, creating a truly enjoyable environment.

You have been teaching architecture, both at Waseda University, where you studied architecture, and at Osaka and Kansai Universities. How is the teaching experience for you?

As a teacher, the most rewarding part is hearing the fresh ideas from young architecture students. They are uninhibited, able to create new styles, techniques, and proposals. Brainstorming during design studio weeks is always a memorable and valuable experience. Teaching reminds me of Dōgen Zenji’s practice of “Great Realization”—a way of seeing the world filled with endless potential.

How have you dealt with daylight in architecture during your studies and as a teacher? How important is this learning process for students’ future as architects?

Daylight is crucial in architecture, influencing how we perceive and interact with space. In my view, architecture should adapt to the natural flow of life, creating environments that enhance well-being without disrupting the community.

In projects like See Sea Park and Think Stay Mt., the interaction between sunlight and architectural elements creates welcoming and enjoyable spaces. This concept of flow emphasizes the importance of designing for both brightness and darkness. The positioning of windows and openings is vital; they serve as connections between the interior and exterior.

Understanding and realizing the atmosphere created by daylight is essential for students’ development as architects. This learning process not only fosters creativity but also prepares them to design environments that harmonize with their surroundings.

Japanese houses often appear dark due to limited sunlight access, especially traditional Machiya houses that typically receive light only from the front and back. These houses are designed with timber pillars and roofs but lack walls, relying on deep eaves to create openings.

While modern architects are drawn to the composition of daylight in these homes, projects like See Sea Park and Think Stay Mt. offer a different philosophy. They incorporate open spaces and transparent units that allow for a seamless connection with nature, utilizing daylight, wind, and thermal flow.

"Understanding and realizing the atmosphere created by daylight is essential for students' development as architects."

How do you see the role of architecture evolving in the next decade, especially in relation to the challenges of climate change?

Climate change is a pressing issue that we must address immediately. As humans, we have a natural tendency to create, but we should focus on developing solutions that do not harm the environment and help sustain both the planet and human society.

For instance, I envision adding artificial agricultural facilities to projects like See Sea Park and Think Stay Mt. This approach allows us to produce food with minimal environmental impact. Creating a flexible product complex can significantly reduce energy, resource, manpower, and time consumption. However, I find that advancing these types of projects is challenging; they are not primarily for business enterprises but for the benefit of future societies.

I am committed to developing sustainable projects, even if it requires taking risks as a developer. Think Stay Mt. exemplifies this approach; we designed it not only as architects but also as owners, operators, and even constructors. While setting up each project is difficult, we must pursue them for the benefit of society, particularly for future generations.

Has your design philosophy changed since you began your practice?

Architecture is not art, though it certainly requires an artistic sensibility. Our work would not be possible without clients, so, first and foremost, architecture must serve them. At the same time, it must also serve society. We always keep in mind what we can offer and how to safeguard our clients’ interests. However, we also recognize our responsibility to society at large, as architecture remains a visible part of the environment throughout its lifespan. Looking ahead, we aim for our architecture to endure the test of time.

Architecture is not a fixed solution; it’s a choice made from countless possibilities. However, confidence in the guiding principles and the selection of the best solution for everyone involved must be ensured by all those who contribute to the realization of the project.

My belief is that the concept of flow and sustainability should be at the core of my work. I was deeply inspired by Arcosanti, Paolo Soleri’s visionary project, during the visit with Tadao Ando. This experience heightened my commitment to protecting and preserving our planet.

Find out more about the works of Osamu Morishita Architects on their official website.